This publication is part of a project to monitor the implementation of the Forest Code in Brazilian states. The report provides a detailed analysis of state regulations and identifies actions underway in the states. It highlights progress made to date and the strategies enacted by states that are farther ahead, as well as key gaps and challenges, and opportunities to accelerate the implementation of the law. This information is reviewed and updated annually. The first edition of this report was published in 2019. This report reviews and updates all data and information therein, emphasizing the progress made in 2020.

There is currently an important opportunity to align agricultural growth and natural resource protection in Brazil. According to estimates, Brazil can double its crop yield by taking advantage of areas that have already been cleared, without the need for additional deforestation.1 The Native Vegetation Protection Law (No. 12,651/2012), also known as the Forest Code, is a crucial instrument to promoting Brazil’s efforts in this law.

Implementing the law, however, remains a major challenge. Eight years after the Forest Code was enacted, it still has not been effectively implemented across all Brazilian states. The year 2020 will be forever characterized by the COVID-19 pandemic imposing the need for organizations and individuals to adapt to a new reality. Quarantines have changed the pace of the economy and imposed a new way of working, with considerable impact on government actions and priorities at all levels. The states’ implementation of the Forest Code was no exception, and its progress across the country was impacted. Despite this, however, a few states have made important advances.

Researchers from Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-Rio) monitor the implementation of the Forest Code at the state level. They identify successful initiatives states have used to move forward that could potentially be replicated, as well as characterize key challenges policymakers have faced and strategies that can be tailored to address the bottlenecks and specificities of each state. The results of this analysis were published for the first time in 2019. This report reviews and updates all data with information collected in 2020.

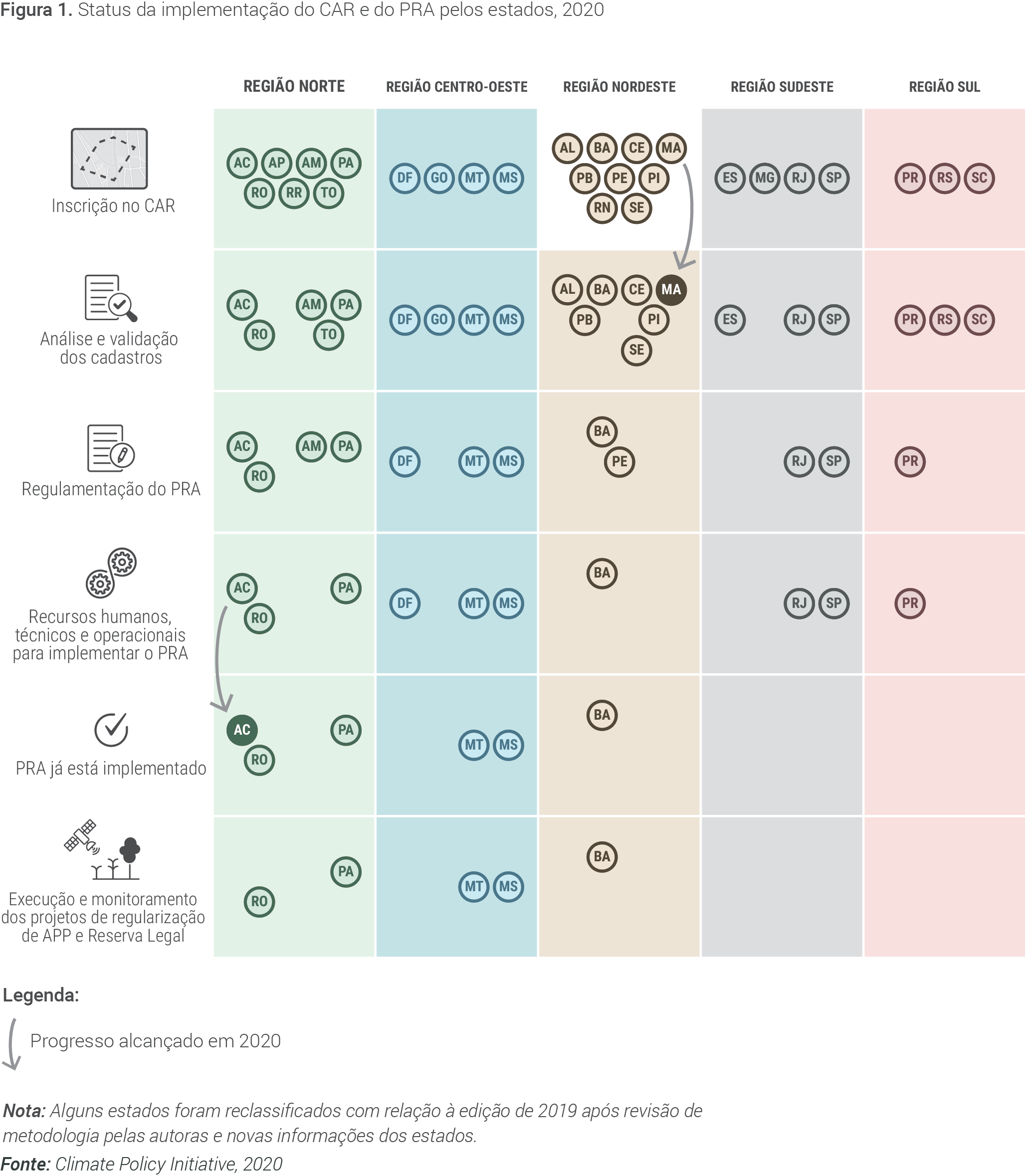

The environmental compliance process for properties is composed of several stages and requires action by different stakeholders. The first steps involve the registration, analysis, and validation of the Rural Environmental Registry (Cadastro Ambiental Rural – CAR), and states also need to regulate and implement the Environmental Compliance Program (Programa de Regularização Ambiental – PRA). Figure 1 below shows the status of each state across all stages of the implementation of the Forest Code and highlights progress for two states, Maranhão and Acre, in 2020.

By 2019, all states had made significant progress in the process of registering properties in the CAR; expanding the CAR database has remained a priority for some states in 2020 as well, like Santa Catarina. Despite this, the registration process for smallholders, possessors, and traditional peoples and communities still requires help from the government in order to move forward. It should be noted that producers must register their rural properties in the CAR no later than December 31, 2020 to be able to join the PRA and benefits from Forest Code’s more flexible rules for consolidated areas in Permanent Preservation Area (Área de Preservação Permanente – APP) and Legal Forest Reserve.

While the analysis and validation stage of the registration process has begun in most states, it remains the main bottleneck to Forest Code implementation. Of the states that had not yet started this phase in 2019, Maranhão has been the only one to implement an “active” routine for validating registrations in 2020. Of the states where the process had already started, only Mato Grosso and Pará saw a significant increase in the number of registrations analyzed per month in 2020. The number of analyses per month in Mato Grosso increased from 300 in 2019 to 5,500 in 2020. The state of Pará analyzed a total of 1,500 registrations per year in 2018 and doubled this figure in 2019. In 2020, Pará reached 3,500 analyses per month and is soon expected to reach 7,000 analyses per month.

The total number of registrations already validated at the state level differs significantly across states. In some states – such as Maranhão, Goiás, Rio de Janeiro, and the Federal District – the number of registrations remains low, between 25 and 150. Other states have made a little more progress and feature between 1,500 to 2,500 validated registrations – such is the case of Amazonas, Ceará, and Rondônia. Mato Grosso and Pará have validated around 5,000 registrations so far, and Paraná stands at around 10,000 registrations. Despite progress in these states, the state of Espírito Santo made the most progress at this stage, validating 72% of the state’s registrations– the equivalent to approximately 70,000 registrations.

Challenges found at this phase include: the high number and low quality of registrations, and scarce cartography data and technical and human resources to perform validation. Five states are still in the enrolment phase and have not yet begun CAR analysis and validation.

Advancing the CAR analysis and validation stage should be a top priority for state governments, since the CAR – as an instrument under the Forest Code – has been used in several other public policies, such as environmental licensing, access to rural credit, and land tenure regularization. The cancellation of over 4,000 registrations in Pará in 2020 highlights the importance of validating CAR information to ensure a reliable registration database.

Twelve states have already enacted norms to institute their PRAs, but none of the states that had not regulated the program last year were able to do so in 2020. The states in this situation have managed some progress, however, with eight of them drafting proposals to regulate their PRAs. Others, however, lag considerably, which also makes them likely to be the ones most impacted by the Federal PRA, set to be implemented by the Federal Government. These states include: Amapá, Espírito Santo, Paraíba, Piauí, Rio Grande do Sul, and Sergipe.

In most states, the PRA is far from operational. The PRA has only been effectively implemented in six states, with a fully operational system, signed commitment agreements, and plans for compliance being executed and monitored in APPs and Legal Forest Reserves. Of the states that had not yet effectively implemented the program last year, only Acre has advanced in 2020. As for the number of commitment agreements signed and in execution in the states, numbers range from 100 to 200 in Acre, Pará, and Rondônia; more than 500 commitment terms were signed in Mato Grosso alone.

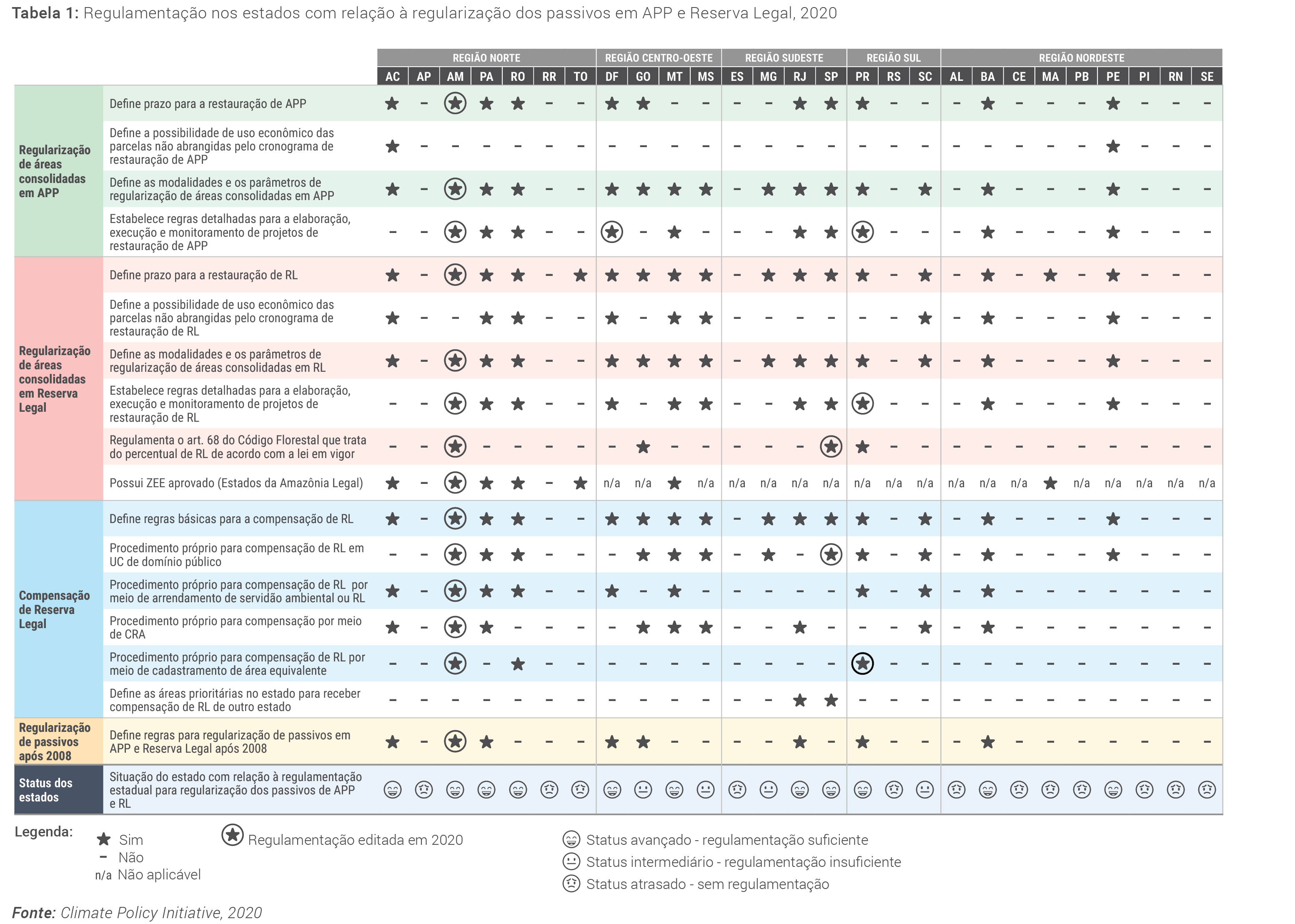

PRA implementation also depends on the states’ regulation of environmental compliance of APPs and Legal Forest Reserves consolidated areas in case there is liability. Table 1 summarizes the status of all states regarding this legislation, defining methods and parameters for forest restoration in APPs and on Legal Forest Reserves

Most states have already established minimum rules for the restoration of APPs and Legal Forest Reserves; however, the twelve states that had not established any rules for environmental compliance in APP and Legal Forest Reserves in 2019, have not advanced significantly in 2020. Only Paraná, whose regulatory framework was insufficient, made progress in 2020 by enacting complementary norms.

Some states have instituted legal rules, establishing guidelines and criteria for the preparation, execution, and monitoring of restoration projects for native vegetation in degraded and altered areas, while others are addressing the issue by means of manuals and booklets.

Legal Forest Reserve compensation, via the donation of a private area within a public Conservation Unit (official protected area) to the state or federal government, has been a key focus area, with regulations in place in 12 states so far. São Paulo, for example, created the Agro Legal Program in 2020, expressly establishing Legal Forest Reserve compensation through donations of areas in Conservation Units as one of the program guidelines, which should be facilitated.

State-level regulation and implementation of Forest Code article 68, which allows for the application of the percentage of Legal Forest Reserve according to the law in force when the vegetation was cleared, remains complex and difficult to execute. Few states have regulated this provision in state law; most states only refer to the federal law. São Paulo, for example, has passed a state law with a list of legal frameworks that must be considered in Legal Forest Reserve calculations at the state level. This provision was deemed constitutional by the São Paulo State Court of Justice in 2019, but the Public Prosecution Service (Ministério Público) filed an extraordinary appeal challenging the decision before the Supreme Federal Court. The Supreme Court’s decision on this appeal will carry great weight, as it will ascertain the competence of the states and the criteria they will use when legislating and determining legal frameworks for enforcing article 68.

When regulating PRAs, most states only provide for the compliance procedures for APP and Legal Forest Reserves deforested areas prior to 2008. Only eight states have passed legislation on the compliance procedures for deforested areas after 2008. Among them, Acre, Bahia, Pará, and the Federal District stipulate that deforested areas before and after 2008 will follow compliance under the PRA. Rio de Janeiro and Paraná have put different procedures in place. Though there is no express legal provision on the matter, some states, like Rondônia, are resolving this issue directly in the CAR and PRA systems.

In addition to state actions put in place this year, other activities executed at the federal level in 2020 may impact the implementation of the Forest Code in the states, sometimes bolstering the law – e.g., initiatives in the financial sector and by the Brazilian Forest Service (SFB) – and sometimes hindering it – e.g., uncertainties regarding the federal PRA and legislative proposals to amend the Forest Code.

Entities and institutions in the financial system launched initiatives in 2020 to foster and accelerate the implementation of the Forest Code. To stimulate progress in CAR validation, the National Monetary Council (Conselho Monetário Nacional – CMN) has included a provision in Brazil’s Agricultural Plan (Plano Safra) 2020/21 to increase the credit limit by 10% for producers with validated CAR. In this initiative, producers with validated CAR gain special access to subsidised resources. This also encourages states to move forward in the validation process so their producers can enjoy the benefit as well. More recently, the Central Bank (Banco Central – BC) announced a Sustainability dimension to the BC# Agenda, with detailed guidelines for allocating public funds with a focus on agribusiness sustainability. The process is still rather incipient, but it can be used to create other incentives for the implementation of the Forest Code.

Another advancement in 2020 was the role played by the Brazilian Forest Service (Serviço Florestal Brasileiro – SFB) in developing an information technology system and infrastructure for the implementation of the CAR and PRA modules. Until 2019, only the registration module was available; this year, however, the SFB has worked to develop and improve the dynamic analysis and environmental regularization modules, which should be made available to the states in 2021.

On the other hand, with the imminent arrival of the December 31, 2020 deadline, after which rural owners and possessors in the states that have not implemented a PRA will be allowed to join the federal PRA, a big question mark looms as the instrument has not yet been regulated. The law does not define or set parameters for what should be considered an “implemented PRA”, and the federal PRA does not seem to conform to the system set forth by the Forest Code, which designates the task of implementing PRAs to the states and circumscribes the role of the Federal Government as merely a coordinator and supporter of state actions. The potential impact of this legal provision on states that have not yet implemented their own PRAs is unknown, which generates considerable uncertainty.

Lastly, the rate of proposed amendments to the Forest Code submitted to National Congress did not slow down in 2020. One such example is Legislative Bill 2,429/2020, brought before the Chamber of Deputies amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, while National Congress was operating in a remote deliberation system, and which increases the amnesty granted to rural landowners who have breached the law, and has a significant impact on the protection of areas designated as Legal Forest Reserves. It is essential that no amendment to the Forest Code be proposed without a very careful assessment of the potential impacts such changes may have on the implementation of the law at the state level. Any legislative change that causes a significant revision of state rules would be tantamount to ignoring all the efforts and resources put in place by the states to regulate and implement such norms, in addition to delaying the implementation of the Code and the environmental compliance of rural properties.

[1] Antonaccio, Luiza, Juliano Assunção, Maína Celidonio, Joana Chiavari, Cristina L. Lopes, Amanda Schutze. Ensuring Greener Economic Growth for Brazil. Rio de Janeiro: Climat