Introduction

Artisanal gold mining (gold garimpo)[1] has long been intertwined with the history of the Amazon. Gold is the most extracted mineral due to its ease of sale and high value. Today, 92% of the area mined in Brazil—both legally and illegally—is concentrated in the Amazon region, and 85% of the country’s garimpos are dedicated to gold extraction.[2] Garimpo is associated with considerable socio-environmental impacts, including deforestation, violence, conflict with traditional peoples and mercury contamination, as well as slave labor, tax evasion, and foreign exchange avoidance.[3],[4],[5],[6],[7] These impacts are amplified by the high rate of illegal practices.[8]

Following an exponential increase in illegal garimpo between 2018 and 2022, the current federal government has devoted special attention to the issue. Garimpo areas on Indigenous Lands and in restricted protected areas where mining activities are prohibited by law grew by 190% during this period.[9] Numerous actions have been taken to combat the illegal exploitation of mineral resources, especially in the Yanomami Indigenous Land region in the Brazilian states of Amazon and Roraima.[10]

However, the negative impacts of garimpo do not stem only from the illegal extraction of minerals. While the activity is regulated in Brazil, mainly by the Mining Code,[11] by Law no. 7,805 of 1989,[12] and by the rules of the National Mining Agency (Agência Nacional de Mineração – ANM), the regulations are anachronistic and subject garimpo to a legal regime that is currently incompatible with the nature of its activities, given that the majority of these enterprises evolved to operate on an industrial and corporate scale, occupying areas similar to those of large mining companies. In addition, undue flexibility in environmental licensing at the state level and a lack of transparency in the implementation of socio-environmental safeguards weaken control of the activity.

In this publication, researchers from Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-RIO) and Amazon 2030 analyze the main environmental protection rules related to garimpo and identify that legal garimpo does not comply with the necessary safeguards to prevent or mitigate socio-environmental damage in the Amazon. This document includes recommendations for improving regulations at both federal and state levels. It also highlights the risk that legislative bills currently before Congress will deepen the mismatch in mining regulations by facilitating garimpo without correcting existing distortions.

Key Findings

Analysis carried out by CPI/PUC-RIO using data from ANM shows that areas with permits for legal gold garimpo in the Amazon have increased since 2016. In fact, around 82% of the authorized areas for gold garimpo in Brazil were established in this region between 2016 and 2023. During this period, of the 770,464 hectares approved in the national territory for gold garimpo, 630,020 hectares are located in the Legal Amazon.[13] The states of Pará and Mato Grosso account for 35% and 64% of this regional total, respectively.

In this context, researchers identified that artisanal gold miners (garimpeiros), when organized in cooperatives, play the leading role in legal garimpo in the Amazon.On average, these cooperatives have exploration areas equivalent to 178% of the areas mined by individual garimpeiros and individual garimpeiro firms combined and are more than twice the size of the areas of the mining industries. This tendency, coupled with the high investment required for mining activity,[14] indicates that garimpo has transformed from an artisanal practice to a business and industrial enterprise, thus requiring strengthened legislation and environmental protection.

Analysis of the main environmental protection rules related to garimpo indicates that the impact of this activity in the Amazon exceeds that of illegal gold mining and that regulatory improvements are needed at both federal and state levels.

At the federal level, the regulatory framework for garimpo, especially in the case of cooperatives,needs to incorporate the requirement for prior discovery, which entails studies to define the location of mineral deposits and determine its economic viability, currently only mandated for industrial mining.This measure would enable better monitoring of the socio-environmental damage caused by the activity and of gold laundering.

It is also essential to shelve bills currently before Congress that would make it even easier to carry out garimpo operations without improving the concept of garimpo or correcting existing distortions in the regulations.

In addition, the states have an important role in mitigating the socio-environmental impacts of legal garimpo of gold in the Amazon. Pará is the most relevant state for improving this agenda due to its national and regional prominence in terms of areas permitted for gold garimpo, the extent of its forest cover, the number of gold garimpo sites that can be legalized, and, above all, state regulations that simplify environmental licensing and loosen socio-environmental controls of the activity.

Despite the fact that the legislation classifies mining as a high-impact enterprise, with three-stage licensing being the general rule at the federal level, in Pará, environmental licensing for garimpo has been simplified and delegated to municipal authorities, an issue that is under discussion in the Brazilian Supreme Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal – STF).[15] The state licensing application process is a single-phase and only requires studies that are normally mandated for low-impact activities, which does not align with the current nature and scale of gold garimpo. These streamlined environmental licensing procedures and/or the insufficient capacity of municipal licensing bodies to carry out the necessary analyses hinder the prevention and mitigation of garimpo-related socio-environmental damage.

Furthermore, a lack of transparency hinders understanding how the socio-environmental safeguards of legal garimpo are implemented in practice. Licensing processes in Pará are scattered between municipalities, and ANM restricts access to information about the activity. These information gaps prevent the monitoring of the application of regulations and weaken the inspection of the socio-environmental damage caused by garimpo.

Overview of ANM Permits for Gold Garimpo

The Mining Code provides for two main types of mining rights that relate to mining activity in the Amazon: Garimpo Permit (Permissão de Lavra Garimpeira – PLG), which applies to garimpo,[16] and the Mining Concession (Concessão de Lavra – CL), which applies to industrial mining.[17]

A PLG can be obtained by individual garimpeiros, individual garimpeiro firms, and garimpeiro cooperatives.[18] This type of license allows the immediate exploitation of a mineral deposit without requiring any prior mineral discovery,[19] though the ANM may occasionally order such studies to be carried out.[20] A Mining Concession, on the other hand, can only be obtained by mining industries after discovery has been carried out.[21]

The main requirement for legal garimpo activities, therefore, is to obtain a PLG from the ANM. However, prior environmental licensing is a condition for obtaining a PLG.[22]

PLGs Approved and Profile of Holders

This study analyzed the 8,589 PLG applications processed for gold extraction in the ANM database between 2000 and 2023.[23] During this period, 2,345 PLGs were approved for gold mining in Brazil, covering a total of 1,054,906 hectares.

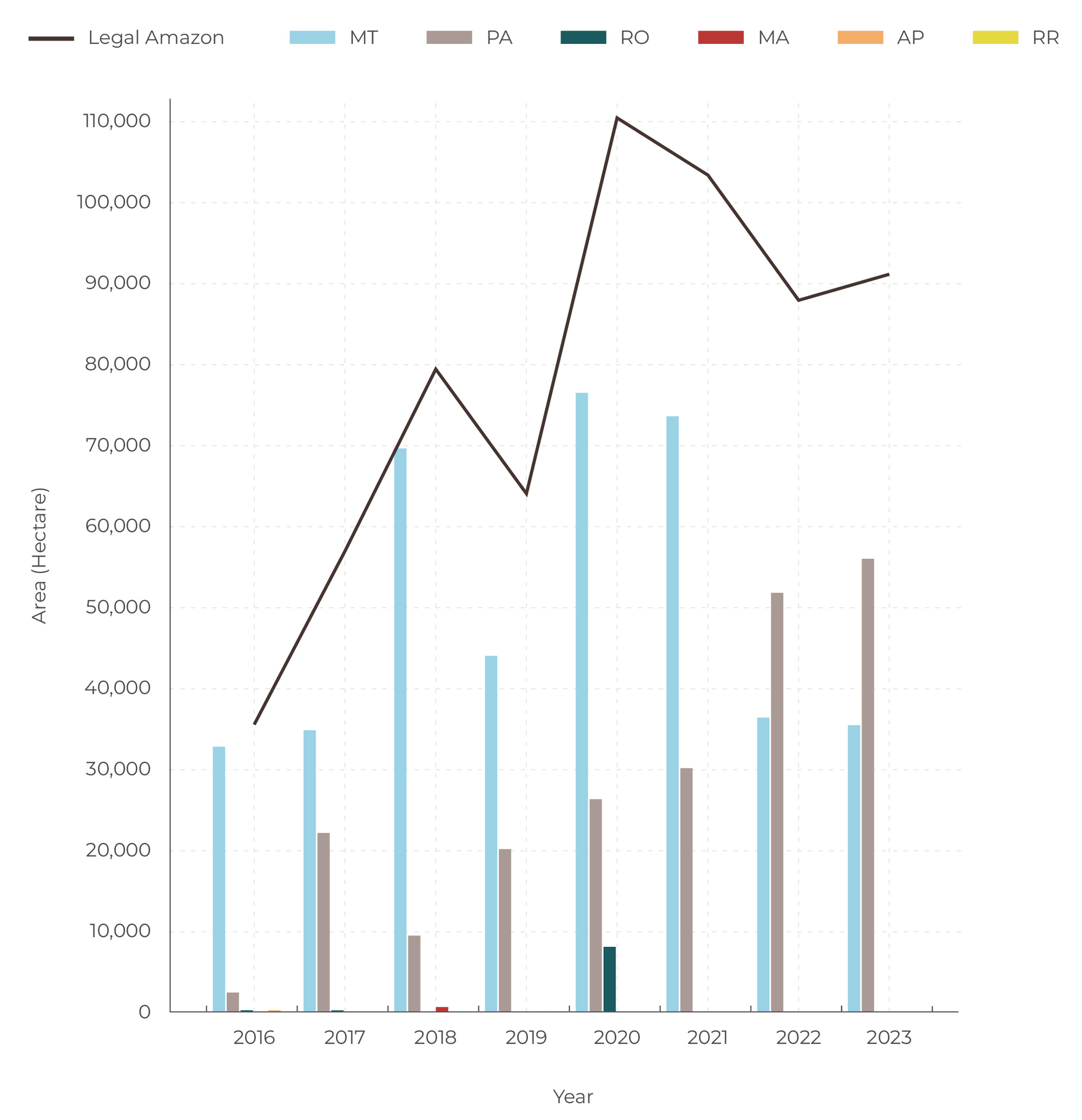

Since 2016, there has been a continuous increase in the number of areas with permits for legal garimpo of gold in the Amazon (Figure 1). Between 2016 and 2023, approximately 82% of the authorizations for gold garimpo in Brazil were granted in the Legal Amazon. Of the total of 770,464 hectares approved for this activity in Brazil, 630,020 hectares are in this territory. Pará and Mato Grosso account for 35% and 64%, respectively, of the regional total.

Figure 1. Area Coverage of PLG Approvals for Gold in the Legal Amazon, 2016–2023

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO with data from ANM (2024), 2025

As described above, PLG applicants can be individuals, individual firms, or cooperatives. However, according to the analyzed data, the PLG area for gold extraction by cooperatives in the Legal Amazon between 2016 and 2023 were equivalent, on average, to around 178% of the area of individuals and individual firms combined. Of the total of 630,020 hectares approved between 2016 and 2023, 403,369 hectares were owned by cooperatives, 226,601 hectares by individual firms, and 49 hectares by individuals.

In Pará, during the period analyzed, most of the licensed areas went to a small number of entities. The top 10% of PLGs (27 permits) covered 107,666 hectares, while the remaining 90% (318 permits) covered just 23,122 hectares. All 27 permits in the top 10% category were granted to cooperatives, while the remaining 90% mostly went to individuals and individual firms. As a result, a few cooperatives obtained 8% of the permits and around 80% of the legal gold garimpo areas in the state.

This reflects the results of the previous CPI/PUC-RIO study in 2022, which found that each cooperative owned, on average, more than twice the area that each mining industry owned under a Mining Concession.[24]

This data, coupled with the high investments required for garimpo,[25] corroborates the hypothesis that cooperatives of garimpeiros are operating in a similar manner to mining industries, but taking advantage of legal benefits while avoiding the stricter regulations applicable to industrial mining.

Lack of Prior Discovery and Backward Trend in Federal Legislation

Lack of Prior Mineral Discovery

As mentioned above, a PLG permits the immediate exploitation of mineral deposits without requiring prior mineral discovery, though the ANM may exceptionally order for such studies to be carried out. A Mining Concession, on the other hand, can only be obtained by mining industries after mineral discovery has been carried out.

Prior mineral discovery involves carrying out the necessary work to define the location of the deposit and determine its economic viability, such as geological, geophysical, and geochemical surveys; physical and chemical analysis of samples; and ore processing tests.[26] These are expensive, time-consuming procedures with low chances of identifying viable mineral deposits. On the other hand, when they do locate a deposit, they make it possible for mineral exploitation to take place in a more planned and concentrated manner in the territory, which tends to limit socio-environmental damage.

The exemption from prior discovery for garimpo stems from an outdated and poorly defined concept of this activity. The original legislation was intended for garimpo that is carried out in an artisanal way by underserved communities. However, the concept of garimpo is subject to confusing definitions in the applicable regulations, which is also relevant to the socio-environmental impacts of garimpo.

The Mining Code defines garimpo as an individual and rudimentary mining activity. This definition, which has existed since the first Mining Code in 1934, comes from the historical conception of the garimpeiro as someone using pickaxes and beaters or, at most, manual devices and portable machines to extract noble metals and precious stones. The definition also aims to protect the garimpeiro as an economically disadvantaged and vulnerable professional.[27],[28] On the other hand, Law no. 7,805 of 1989 and the Garimpeiro Statute tautologically define garimpo (as an activity) as the exploitation of minable minerals carried out in garimpos (as a place), and make no reference to this activity being rudimentary in nature.[29],[30] According to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministério Público Federal – MPF), the differences between definitions create a conceptual indeterminacy that has the potential to lead to the practice of industrial mining being concealed as garimpo.[31]

The regulation, in fact, allows garimpo to be carried out not only by individual garimpeiros—who are economically disadvantaged, vulnerable, and use rudimentary tools—but also by cooperatives of garimpeiros—which operate across areas that are identical in size to those of mining industries. Although such activities could have socio-environmental impacts similar to those of industries, they are conducted under the same (more lenient) regulatory regime applied to individual garimpeiros, including no mandate for prior discovery in order to obtain a PLG.[32]

This exemption from prior discovery is an inconsistency considering the current reality of garimpo, afforded by the conceptual indeterminacy of the activity in the law. Cooperatives, which hold exploration rights over vast areas and are generally focused on exploration closer to the surface, can cause extensive devastation in the search for and extraction of gold in the Amazon, a scenario that is facilitated by legislative and regulatory gaps. Given this scale, cooperatives could also take on the responsibilities and burdens of industrial mining companies in order to appropriately prevent and mitigate this damage.

According to the MPF, the lack of prior discovery hampers not only the monitoring of the socio-environmental damage caused by garimpo, but also of gold laundering, because it makes it difficult to identify the exact area of mineral exploitation, the way in which the exploitation is carried out, and the amount of gold that this area can produce.[33]

Backward Trend in Federal Legislation

Cooperatives are exempt from carrying out prior discovery due to the inconsistency of the legislation. However, recent efforts to reform the regulation of this activity have not moved toward correcting this distortion but instead have sought to make garimpo even easier without establishing responsibilities compatible with the true nature and scale of activities.

Some examples of this misguided regulatory policy are two federal decrees published in February 2022. One federal decree orders the ANM to establish simplified permitting procedures for small-scale mining ventures.[34] The other decree created the Program to Support the Development of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (Programa de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento da Mineração Artesanal e em Pequena Escala – PRÓ-MAPE) and the Interministerial Commission for the Development of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (Comissão Interministerial para o Desenvolvimento da Mineração Artesanal e em Pequena Escala – COMAPE).[35] While this second decree was revoked by the current government, the first remains in force. Considering that the legislation still treats garimpo as an artisanal and rudimentary activity, the possibility of extending the concept of “small-scale” to benefit cooperatives that operate on a business and industrial scale, with even more streamlined procedures for obtaining PLGs, cannot be ruled out.[36]

More recently, two bills in the National Congress have sought to create even more leniancy and advantages for garimpo without correcting the inconsistencies in the legislation. Bill no. 2,973 of 2023, being discussed in the Senate at the time of writing, aims to allow PLGs to be issued for garimpo operations in areas where there has been previous mineral discovery by mining industries, even if the owners of these areas disagree. It also aims to expand the list of minerals that can be exploited by garimpos to include manganese and copper.[37],[38] The bill’s justification is to make those areas available for “small-scale mining activity,” which would supposedly promote the regularization of clandestine garimpos.[39]

However, there is no guarantee that a small-scale operator, such as a cooperative, will mine within the discovery area in deposits that have already been located, which would, in theory, make it easier to control the activity. On the contrary, it is quite possible that it will operate in other parts of the discovery area in the same manner as it would elsewhere and with the same impacts. Furthermore, even if this cooperative were to share an industrial player’s deposit, allowing this cooperative to do so without incurring any discovery costs goes against the grain of assigning responsibilities and burdens compatible with the nature and scale of garimpo, not to mention the inefficiencies and conflicts that such sharing can cause. Finally, nothing suggests that the changes proposed by the bill would encourage clandestine garimpos to abandon lucrative and unsupervised activities in order to become legalized. It does not seem desirable to pursue legalization that neither results from correcting inconsistencies in the legislation nor guarantees adequate socio-environmental controls of the activities.

While Bill no. 957 of 2024, currently under discussion in the Chamber of Deputies, mainly aims to reform the legal concept of garimpo to characterize it as an activity carried out “regardless of the technique used and the scale of production,” it does not address the benefits already attributed to the activity. In other words, the bill recognizes the change in the profile of garimpo, but does not seek to correct the distortions in the legislation. Instead, it seeks to create additional benefits, such as expanding the list of minerals that can be mined.[40]

Simplified Environmental Licensing for Garimpo in Pará

General Rules on Garimpo Licensing

Environmental licensing is one of the main instruments of environmental protection and is regulated by various interrelated legal norms. It was first provided for in the National Environmental Policy (Política Nacional do Meio Ambiente – PNMA) and expressly accepted by the 1988 Constitution.[41] Complementary Law no. 140 of 2011 sets out how government entities must coordinate to implement licensing.[42] Resolutions from the National Environment Council (Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente – CONAMA) also regulate procedures and establish parameters that must be used by licensing bodies. In addition, states and municipalities have legislation applicable at the regional or local level.

According to the general rules on the subject, environmental licensing of any activity is, as a rule, a three-stage process. The Preliminary License (Licença Prévia – LP) certifies the environmental viability of a project.[43] The LP is issued after an environmental impact assessment has been approved.[44] In the case of undertakings or activities that “effectively or potentially cause significant degradation,” the required assessment is the Environmental Impact Study (Estudo de Impacto Ambiental – EIA) and its Environmental Impact Report (Relatório de Impacto Ambiental – RIMA).[45] After the LP, an Installation License (Licença de Instalaçção – LI) must be issued, which authorizes, for example, the installation of equipment and environmental control measures needed to carry out the activity. Finally, the Operating License (Licença de Operação – LO) is issued, which authorizes the start of the activity.[46]

A legal garimpo can only operate once it has been licensed.[47] All “mineral extraction” activities fall into the category of activities that “effectively or potentially cause significant degradation,”[48] including garimpo, which is classified as a “high pollution potential” activity.[49]

As a result of this classification and in view of the general rules on the subject, garimpo should, as a rule, be licensed under the three-stage regime, with the submission of an EIA/RIMA.

This was confirmed by the authors through consultation with the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis – IBAMA). This consultation was motivated by the existence of a CONAMA rule, which, according to the MPF, had been interpreted by some states to justify simplified licensing for garimpo.[50],[51] However, according to IBAMA, the provisions of this rule are no longer applicable because they are out of date in relation to the Mining Code, so the rule would now only serve to regulate procedural stages.[52]

The Garimpo Licensing in Pará

Pará is the most relevant state for analyzing the socio-environmental impacts of legal garimpo in the Amazon. Despite having about half the area with permission for garimpo of Mato Grosso, Pará has about two and a half times the forest cover of its neighboring state: there are 88.9 million hectares of vegetation cover in Pará compared to 35.6 million hectares in Mato Grosso.[53],[54] Furthermore, if legal and illegal garimpo are taken into account, Pará is the state with the largest exploited area,[55] so discussions about the socio-environmental safeguards of garimpo there may be more important if the activity is legalized. A recent news report helps to measure the presence of garimpo in Pará and the challenges for its socio-environmental control: of 870 PLGs identified in protected areas in Brazil, 846 (97%) are in the state.[56]

In Pará, environmental licensing for garimpo is streamlined even though the state itself classifies the activity as high impact. The simplification is characterized by the fact that the state does not require the three licenses for the activity, nor does it require the EIA/RIMA. By way of comparison, while the state of Mato Grosso recognizes that garimpo has a high level of pollution as well, it requires that the activity must undergo three-stage environmental licensing, with the preparation of an EIA/RIMA.[57],[58],[59]

Although states have the autonomy to regulate the environmental licensing of activities in their territories, the licensing of garimpo in Pará is inconsistent not only in comparison to the general rules for mining licensing, but also in relation to the classification of the degree of impact of garimpo made by the state itself.

Pará’s State Environmental Policy establishes that any type of mineral exploration must obtain “prior licensing from the competent environmental agency” and that garimpo requires “prior licensing from the state’s environmental agency.”[60] A state law and a rule from the Pará State Environmental Council (Conselho Estadual do Meio Ambiente do Pará – COEMA/PA) classify garimpo, respectively, as an activity with “high pollution potential” and ”high polluting/degrading potential.”[61],[62] This is the highest level of impact possible in the classification established by these rules.

However, a rule issued by the State of Pará Secretariat of the Environment and Sustainability (Secretaria de Estado de Meio Ambiente e Sustentabilidade – SEMAS/PA) stipulates that the garimpo operation should be licensed in a streamlined manner by obtaining only an LO and preparing simplified environmental studies, presented in the form of an Environmental Control Report (Relatório de Controle Ambiental – RCA).[63] The RCA is a type of study required for projects with a low environmental impact, which goes against the state’s classification of garimpo’s degree of impact.[64]

It should be noted that a similar rule in the state of Roraima was declared unconstitutional by the STF in 2021 on the grounds that it “deviated from the federal model protection by providing for the existence of a faster and more simplified form of single environmental licensing.” According to the STF, this state rule “weakens the exercise of environmental police power, as it seeks to apply a less effective environmental licensing procedure for activities with a significant impact on the environment, such as garimpo, especially with the use of mercury.”[65]

In addition to the undue simplification of the licensing process in question, in Pará, garimpo operations with areas of 50 hectares or less were classified as having a local impact, and their environmental licensing was delegated by the state to the municipalities.[66] The previous limit was 500 hectares. Municipalization, in the case of high-impact activities, can hinder the prevention and mitigation of socio-environmental damage due to the insufficient capacity of municipal licensing bodies to carry out complex analyses.[67]

Regarding this delegation, the MPF issued a recommendation that “municipal environmental licensing for garimpo projects should not be allowed, taking into account the regional nature of the impacts.” According to the MPF’s understanding, “the competence to license garimpo operations, particularly alluvial garimpo, cannot be delegated to municipalities under any circumstances, given that their impacts go beyond the local level.”[68]

There is no evidence in ANM data that individual garimpeiros or cooperatives have applied for multiple PLGs of up to 50 hectares—or, previously, up to 500 hectares—to avoid state licensing. That is, no public ANM data shows that the same individual, firm, or cooperative has applied for multiple contiguous PLGs in their own name to avoid applying for larger areas and thus benefit from any weaknesses in municipal licensing. However, it could be possible that the PLGs applied for in the name of different individuals are controlled by a single person or cooperative in practice.

The state’s environmental regulations relating to “acts authorizing garimpo activities” were subject to review by COEMA/PA.[69] This did not, however, prevent a lawsuit from being filed with the STF in late 2023, questioning the constitutionality of municipal environmental licensing for garimpo in areas smaller than or equal to 500 hectares in Pará. The lawsuit was filed by the Partido Verde in the form of an Action against a Violation of a Constitutional Fundamental Right (Arguição de Descumprimento de Preceito Fundamental – ADPF).[70] The limit was lowered from 500 hectares to 50 hectares after the lawsuit was filed on September 23, 2024.[71]

The lawsuit alleges the unconstitutionality of the COEMA/PA resolution that established garimpo operations of 500 hectares or less as having a local impact for the purposes of delegating licensing to municipalities.[72] The main argument is that garimpo in areas such as those covered by the resolution would have devastating effects that go far beyond local impact. As such, the lawsuit alleges that the resolution would violate the fundamental rights to a balanced environment, as provided for in the 1988 Constitution, and would ignore STF precedents that reinforce the need for rigorous licensing for activities with a major environmental impact.

Even before the limit was changed from 500 hectares to 50 hectares, Pará filed a challenge to the lawsuit, defending the constitutionality and legality of the resolution. The MPF and the Attorney General’s Office (Advocacia Geral da União – AGU) took a stand in favor of the Partido Verde’s arguments. The rapporteur of the action, Minister Luiz Fux, adopted a summary procedure for the judgment of the action so that there should be no preliminary injunction to suspend the resolution, only a definitive decision on the matter.

Lack of Transparency on Socio-environmental Safeguards

In addition to the inconsistencies in the regulation of garimpo presented in the previous sections, this study also identified a lack of transparency in the environmental licensing processes and in the how licensing is handled by the ANM before the PLG is issued.

This information gap prevents analysis of how the socio-environmental safeguards for garimpo are implemented in practice and the identification of improvements in the sector’s regulations and those pertaining to environmental licensing.

In the case of Pará, the main problem in this regard seems to be the dispersal of processes and information due to the municipalization of licensing. It would be desirable for the full files to be available in a centralized and digitalized form for better monitoring and inspection of the licensing delegated to the municipalities.

As for the ANM, it would be important to understand whether the agency carries out any assessment of the environmental licensing of the garimpo before issuing the PLG since the license is a condition for this issue.[73] In the absence of mandatory prior mineral discovery, the license could possibly provide relevant information for the agency to better supervise the activity. However, the ANM has allowed any information to be considered confidential at the request of PLG process holders.[74] The researchers tried to access information on environmental licensing in ANM’s PLG processes through the Brazilian Law on Access to Public Information (Lei de Acesso à Informação – LAI) and a direct request to the agency’s ombudsman, however the requests were denied on the grounds that the information would be restricted.[75]

Conclusions

Some of the main socio-environmental problems in the Amazon are caused by Garimpos, which constitute a widely-established economic activity in the Amazon region, especially dedicated to the extraction of gold.

In this context, the analysis of the main environmental protection rules for the activity indicates that the impact of gold garimpo in the Amazon goes beyond illegal garimpo and that improvements are needed in both federal and state regulations.

At the federal level, it is necessary to extend the obligation for prior discovery—currently only required for industrial mining—to garimpo activity, especially when carried out by cooperatives that are increasingly acting in an entrepreneurial and industrial way. It is also essential to shelve bills that seek to make garimpo even easier without correcting the distortions in the regulations.

At the state level, it is necessary to implement three-phase licensing and the obligation to prepare an EIA/RIMA for garimpo in Pará, which is the most relevant state for analyzing the socio-environmental impacts of legal garimpo in the Amazon. There also needs to be a cautious reassessment of the capacity of Pará’s municipalities to carry out environmental licensing for this activity.

Finally, there is a need to improve the transparency of the implementation of socio-environmental safeguards for garimpo by making the full licensing processes in Pará available centrally and digitally and reviewing the ANM’s policy on the secrecy of processes.

[1] Garimpo is the term traditionally used to define small-scale artisanal mining in Brazil. Most of the garimpo in Brazil is dedicated to the extraction of gold. This publication employs garimpo as a synonym of small-scale artisanal mining.

[2] MAPBIOMAS. Destaques do mapeamento anual de mineração e garimpo no Brasil de 1985 a 2022: O avanço garimpeiro na Amazônia. 2022. bit.ly/4iLGXFm.

[3] Idrobo, Nicolás, Daniel Mejía, and Ana María Tribin. “Illegal Gold Mining and Violence in Colombia”. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 20 (2013): 83-111. bit.ly/41Vv1LV.

[4] Pereira, Leila and Rafael Pucci. A Tale of Gold and Blood: The Unintended Consequences of Market Regulation on Local Violence. 2021. bit.ly/42h0Z41.

[5] Castilhos, Zuleica, et al. “Human exposure and risk assessment associated with mercury contamination in artisanal gold mining areas in the Brazilian Amazon.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22, no. 15 (2015): 11255-11264. bit.ly/3E4RP2y.

[6] Bastos, Wanderley R. et al. “Mercury in the environment and riverside population in the Madeira River Basin, Amazon, Brazil”. Science of The Total Environment 368, no. 1 (2006): 344-351. bit.ly/4kCOAQe.

[7] Bell, Lee and Dave Evers. Mercury exposure of women in four Latin American gold mining countries: elevated mercury levels found among women where mercury is used in gold mining and contaminates the food chain. IPEN, 2021. bit.ly/3I5jRqu.

[8] Instituto Escolhas. Raio X do ouro: mais de 200 toneladas podem ser ilegais. 2022. bit.ly/3vYPLCU.

[9] MAPBIOMAS. Destaques do mapeamento anual de mineração e garimpo no Brasil de 1985 a 2022: O avanço garimpeiro na Amazônia – Coleção 8. 2022. bit.ly/4iLGXFm.

[10] IBAMA. Two years of federal actions in Yanomami Land: illegal mining plummets and deaths from malnutrition fall by 68%. 2025. Access date: April 2, 2025. bit.ly/4iDs3R6.

[11] Decree-Law no. 227, February 28, 1967. bit.ly/4kK9Eo0.

[12] Law no. 7,805, July 18, 1989. bit.ly/3R1T7y6.

[13] The Legal Amazon is made up of the states of Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, Tocantins and part of Maranhão. Learn more at: IBGE. Amazônia Legal. 2022. Access date: April 2, 2025. bit.ly/41PbNpH.

[14] Instituto Escolhas. Abrindo o livro caixa do garimpo – Sumário Executivo. São Paulo, 2023. bit.ly/3FCXf52.

[15] STF. ADPF 1104. nd. Access date: March 12, 2025. bit.ly/4bOgHYD.

[16] Decree-law no. 227, February 28, 1967. bit.ly/4kK9Eo0.

[17] Ibid., Art. 7 and Art. 36.

[18] ANM Ordinance no. 155, May 12, 2016. Art. 201. bit.ly/4hspkta.

[19] Law no. 7,805, July 18, 1989. Art. 1. bit.ly/3R1T7y6.

[20] Ibid., Art. 6.

[21] Decree-Law no. 227, February 28, 1967. bit.ly/4kK9Eo0.

[22] Law no. 7,805, July 18, 1989. bit.ly/3R1T7y6.

[23] There were a significant number of PLG applications between 1990 (the earliest date from which files are available) and 2000, but they have been disregarded because their areas are much smaller than those of applications after 2000.

[24] Cozendey, Gabriel et al. Presidential decrees exacerbate the contradiction in mining regulations at the expense of the environment. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2022. bit.ly/4jQ7KS9.

[25] Instituto Escolhas. Abrindo o livro caixa do garimpo – Sumário Executivo. São Paulo, 2023. bit.ly/3FCXf52.

[26] Decree-Law no. 227, February 28, 1967. bit.ly/4kK9Eo0.

[27] Ibid., Art. 70, I, and Art. 71.

[28] MPF. Mineração ilegal de ouro na Amazônia: marcos jurídicos e questões controversas. Brasília, 2020. bit.ly/420VgQT.

[29] Law no. 7,805, July 18, 1989. bit.ly/3R1T7y6.

[30] Law no. 11,685, June 2, 2008. bit.ly/4iYYdYw.

[31] MPF, Câmara de Coordenação e Revisão. Mineração ilegal de ouro na Amazônia: marcos jurídicos e questões controversas. Brasília: MPF, 2020. bit.ly/420VgQT.

[32] The maximum area of a PLG for metallic minerals in the Amazon, granted to a garimpeiro cooperative, is identical to the maximum area of a Mining Concession for these minerals in the region: 10,000 hectares. Learn more at: ANM Ordinance no. 155, May 12, 2016. Articles 42, § 1, and 44, II. bit.ly/4hspkta.

[33] MPF, Câmara de Coordenação e Revisão. Mineração ilegal de ouro na Amazônia: marcos jurídicos e questões controversas. Brasília: MPF, 2020. bit.ly/420VgQT.

[34] Decree no. 10,965, February 11, 2022. bit.ly/4huJVwU.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Cozendey, Gabriel et al. Presidential decrees exacerbate the contradiction in mining regulations at the expense of the environment. Rio de Janeiro: Climate Policy Initiative, 2022. bit.ly/4jQ7KS9.

[37] According to Law no. 7,805 of 1989, “gold, diamond, cassiterite, columbite, tantalite, and wolframite, in their alluvial, eluvial and colluvial forms, are considered to be garimpo minerals; sheelite, other gems, rutile, quartz, beryl, muscovite, spodumene, lepidolite, feldspar, mica and others might also be, in types of occurrence that may be indicated, at the discretion of the National Department of Mineral Production – DNPM”. Learn more at: Law no. 7,805, July 18, 1989. Art. 10, § 1. bit.ly/3R1T7y6.

[38] The DNPM was replaced by the ANM, which refers only to art. 10, § 1, of Law 7.805/1989 when mentioning garimpo minerals. Learn more at: ANM Ordinance no. 155, May 12, 2016. Art. 204, IV. bit.ly/4hspkta.

[39] Bill no. 2973, 2023. bit.ly/3Dzm9SI.

[40] Bill no. 957, 2024. bit.ly/43FX0Ac.

[41] Law no. 6,938, August 31, 1981. bit.ly/3DO3zWV.

[42] Law no. 140, December 8, 2011. bit.ly/3HwoyvU.

[43] CONAMA Resolution no. 237, December 19, 1997. bit.ly/3DOXp8W.

[44] Ibid., Art. 10.

[45] Ibid., Art. 3.

[46] Ibid., Art. 8, II and III.

[47] Law no. 7,805, July 18, 1989. bit.ly/3R1T7y6.

[48] CONAMA Resolution no. 1, January 23, 1986. bit.ly/4hz4vMK.

[49] Law no. 6,938, August 31, 1981. bit.ly/3DO3zWV.

[50] CONAMA Resolution no. 9, December 6, 1990. bit.ly/4kKno24.

[51] According to the MPF: “(…) it can be seen that CONAMA’s Resolution 09/1990, as a rule, subjects any form of mineral exploration to the prior preparation and approval of an Environmental Impact Study and Environmental Impact Report (EIA/RIMA)—except, apparently, in the case of garimpo. (…) The loophole created by CONAMA, which excludes garimpo from the rules of Resolution 09/1990, without adopting specific rules for this activity, has the practical consequence of spreading the idea that, in the case of environmental licensing of garimpo, , the Environmental Impact Study and the Environmental Impact Report (EIA/RIMA) would be dispensable, and could be replaced by simplified studies.” Learn more at: MPF, Câmara de Coordenação e Revisão. Mineração ilegal de ouro na Amazônia: marcos jurídicos e questões controversas. Brasília: MPF, 2020. bit.ly/420VgQT.

[52] According to IBAMA, in response to the consultation: “CONAMA Resolution 09/1990 was aimed at the environmental licensing of mineral substances previously classified as Class I, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII and IX by the Mining Code (Decree Law 227/1997). With the repeal of this classification by Law 9.314/1996, the aforementioned Resolution lost its purpose. However, it is not uncommon to consider some of the procedures set out in this Resolution only for the purposes of reconciling the stages that make up mineral management (the responsibility of the ANM) and environmental management (the responsibility of the environmental agency) without, however, taking into account the classification of minerals that was once revoked. (…) In this context, all environmental licensing of mining activities, including garimpo, has the general procedure, within the scope of federal environmental legislation, guided by CONAMA Resolution 237/1997, as well as the EIA/RIMA requirement guided by CONAMA Resolution 001/1986.” Learn more at: IBAMA. Resposta SIC e OUV – 11727427. 2022. Access date: March 12, 2025. bit.ly/42sBYnJ.

[53] MAPBIOMAS. Plataforma MapBiomas uso e cobertura. nd. Access date: March 22, 2025. bit.ly/3DLLith.

[54] This data on forest cover does not include savannah formations, mangroves, flooded forests and restinga trees.

[55] MAPBIOMAS. Destaques do mapeamento anual de mineração e garimpo no Brasil – 1985 a 2022: O avanço garimpeiro na Amazônia – Coleção 8. 2022. bit.ly/4iLGXFm.

[56] Marchesini, Lucas and João Gabriel. ANM autoriza 870 garimpos em unidades de conservação ambiental. Folha de S. Paulo. 2024. Access date: March 12, 2025. bit.ly/3DCLgny.

[57] Law no. 38, November 21, 1995. Art. 23. bit.ly/3Dykmxh.

[58] Decree no. 1,268, January 25, 2022. bit.ly/3DzD7Aq.

[59] Decree no. 1,585, December 21, 2022. bit.ly/44eS85k.

[60] Law no. 5,887, May 9, 1995. bit.ly/3FoKknr.

[61] Law no. 7,596, December 29, 2011. bit.ly/3R676Tu.

[62] COEMA/PA Resolution no. 162, February 2, 2021. bit.ly/3R2xddY.

[63] SEMAS/PA Normative Instruction no. 006, July 3, 2013. bit.ly/4hu95vy.

[64] MMA-PNLA. Estudos ambientais. nd. Access date: March 12, 2025. bit.ly/4iq75G5.

[65] State Law no. 1,453 of 2021 established “specific procedures and criteria for Environmental Licensing of Garimpo Activities in the State of Roraima.” In its decision, the STF unanimously found that there had been both “an infringement of the Union’s competence to issue general rules on environmental protection” and “usurpation of the Union’s exclusive competence to legislate on mining”. Learn more at: STF. ADI 6672/RR – Roraima. 2021. Access date: April 2, 2025. bit.ly/41WY6X7.

[66] COEMA/PA Resolution no. 162, February 2, 2021. bit.ly/3R2xddY.

[67] Abreu, Emanoele L. and Alberto Fonseca. “Comparative analysis of environmental licensing decentralization in municipalities of the Brazilian states of Minas Gerais and Piauí”. Sustainability in Debate 8, no. 3 (2017): 167-180. bit.ly/3EzmW6K.

[68] MPF. Recomendação no. 01/2023 GAB/PRM/ITB/STM. 2023. bit.ly/4iqGDfq.

[69] COEMA/PA Resolution no. 177, April 13, 2023. bit.ly/41Hvxvr.

[70] STF. ADPF 1104. nd. Access date: March 12, 2025. bit.ly/4bOgHYD.

[71] COEMA/PA Resolution no. 183, September 23, 2024. bit.ly/3DxQJw1.

[72] COEMA/PA Resolution no. 162, February 2, 2021. bit.ly/3R2xddY.

[73] ANM Ordinance no. 155, May 12, 2016. bit.ly/44eUHV0.

[74] ANM Resolution no. 1, January 25, 2019. bit.ly/3DL8tUA.

[75] Fala.BR. Pedido de acesso à informação no. 48003.001926/2023-13. March 27, 2023.

This work is supported by a grant from Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI), Institute Climate and Society (iCS), and Itaúsa Institute. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of our partners and funders.

The authors would like to thank Eduardo Minsky for collecting data from ANM; Luiza Antonaccio, Nina Didonet, Natalie Hoover, Juliano Assunção, Beto Veríssimo, and the participants of the Amazon 2030 project virtual meetings for their comments and suggestions; and Bruna Fernandez and Gaia Hasse for their preliminary research that supported the preparation of this document. We would also like to thank Kirsty Taylor, Natalie Hoover, Giovanna de Miranda, and Camila Calado for their work in reviewing and editing the text, and to Meyrele Nascimento and Nina Oswald Vieira for their graphic design work.