The Indonesia Net Zero Emission (NZE) Roadmap for the energy sector, launched by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) in September 2022, has laid out the plan to eliminate coal-fired power as a national energy source by 2030 and achieve 87% renewable energy mix by 2060. New energy sources, such as nuclear, make up the remaining 13%. Achieving this target will require investment in renewable energy of around USD 16 billion annually, far from current levels of investment or even the stated commitments towards renewable energy investment.

CPI’s most recent tracking of Indonesia power sector finance shows renewable energy finance only reached USD 3 billion per annum from 2015 to 2021, suggesting that investments must increase by more than five times to meet Indonesia’s NZE 2060 scenario. To better understand this gap, and ways to address it, CPI examines two key areas — the financing gap and the corresponding energy capacity gap — as well as opportunities to better align power sector finance with Indonesia’s NZE 2060 commitment.

Landscape of Indonesia Power Sector Finance

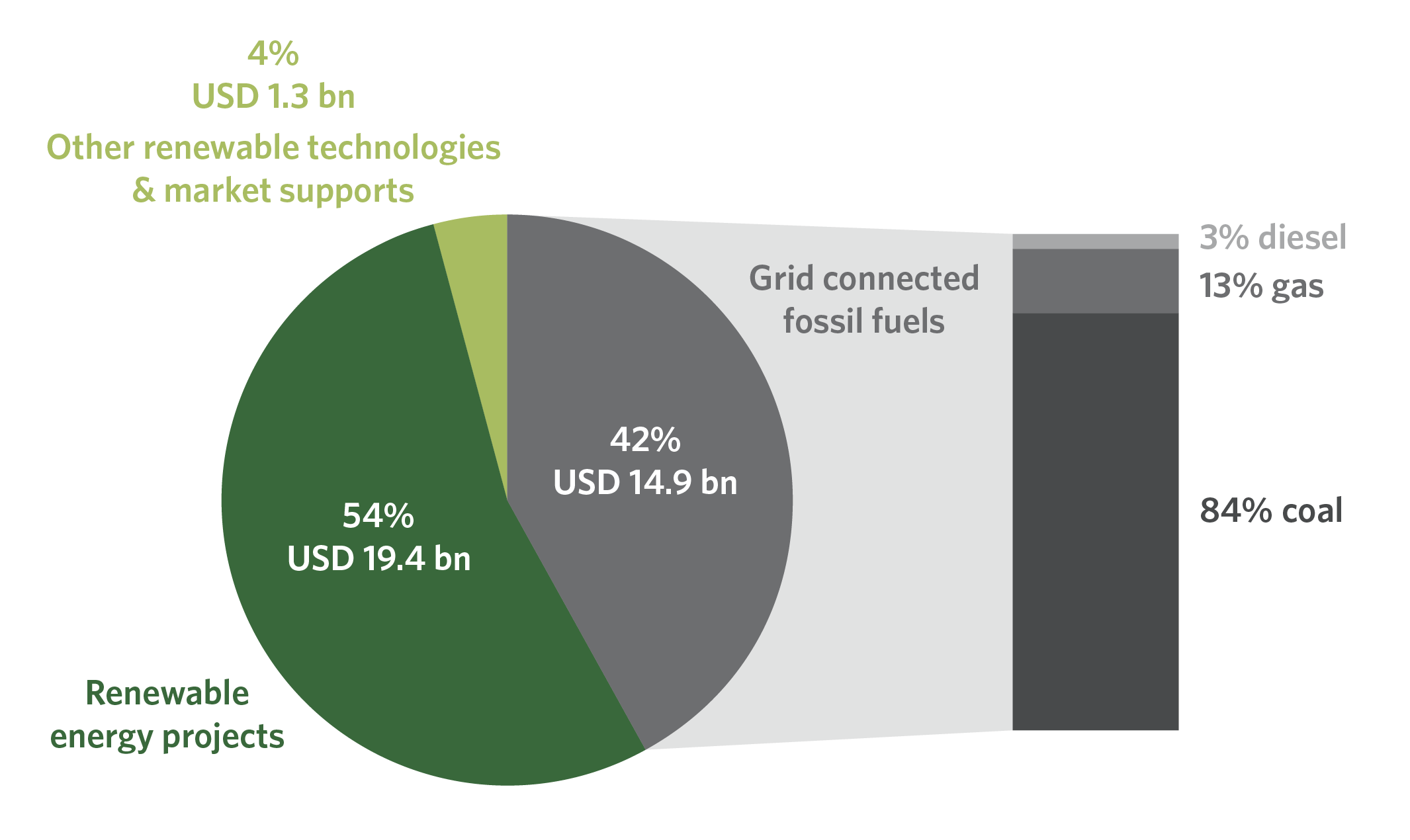

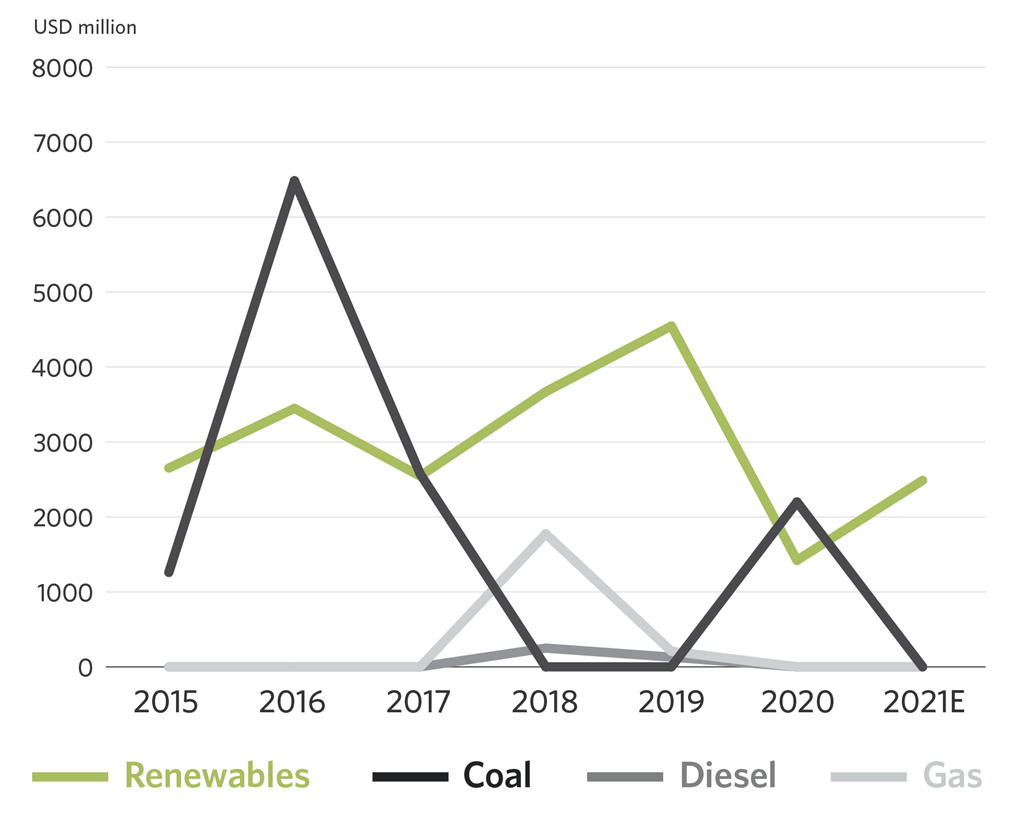

Total tracked finance commitment across all of Indonesia’s power sector from 2015 to 2021 stands at USD 35.6 billion, or approximately USD 5 billion annually on average. Renewable energy now accounts for 58% of power sector finance, increasing significantly during the overall period, but experiencing a notable setback in 2020 as the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the lack of renewable energy support in the economic recovery stimulus rendered new investments in renewable energy less attractive (Vivid Economics and CPI, 2021)[1].

Figure 1. Total tracked finance commitment for Indonesia’s power sector from 2015 to 2021

In parallel, coal investment surged due to policy signals from Indonesia’s 2020 Omnibus, which eased coal mining permit extension and removed royalty obligations for downstream coal mining, as well as the ongoing 35 GW power generation programme mandating at least 45% of new energy plants to be coal powered.

Figure 2. Indonesia’s renewable energy finance from 2015 to 2021

Despite those policy issues, renewable energy finance rebounded in 2021 with a new commitment of USD 2.5 billion, primarily targeting the enabling environment and ecosystem, such as technology, policy making, and feasibility studies. On the other hand, no new fossil fuel finance commitment was recorded in 2021. This was driven by the more recent and NZE pertinent policies such as Indonesia’s Long-Term Strategy for Low Carbon and Climate Resilience (LTS-LCCR) and Sustainable Finance Roadmap Phase II that incentivize investment shift from fossil fuels to renewables. The newly launched Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) and Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) have further strengthened the momentum for both accelerating power sector decarbonization and scaling up renewable energy finance.

Renewable Energy Finance and Capacity Gaps

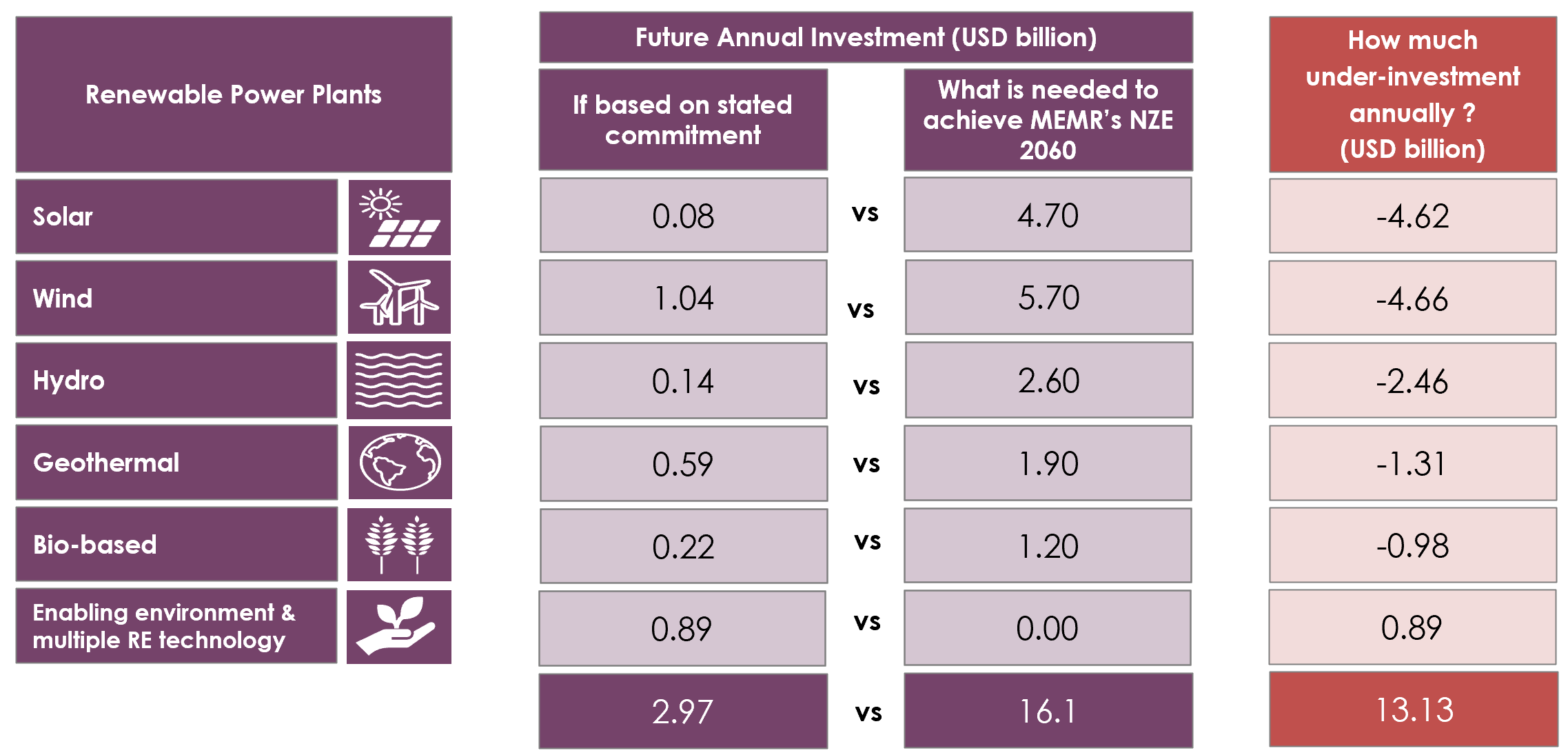

Despite the upward trend in renewable energy investment in the past few years, the gap between committed finance and what is needed is growing. In addition to the economic impact of COVID-19, this widening gap can be attributed to uncompetitive feed-in tariffs for renewables, locked-in coal investments, and prolonged fossil fuel subsidies (currently at an annual average of USD 135 million since 2015[2]).

Figure 3. Projected annual finance gap of the power sector to meet NZE Scenario

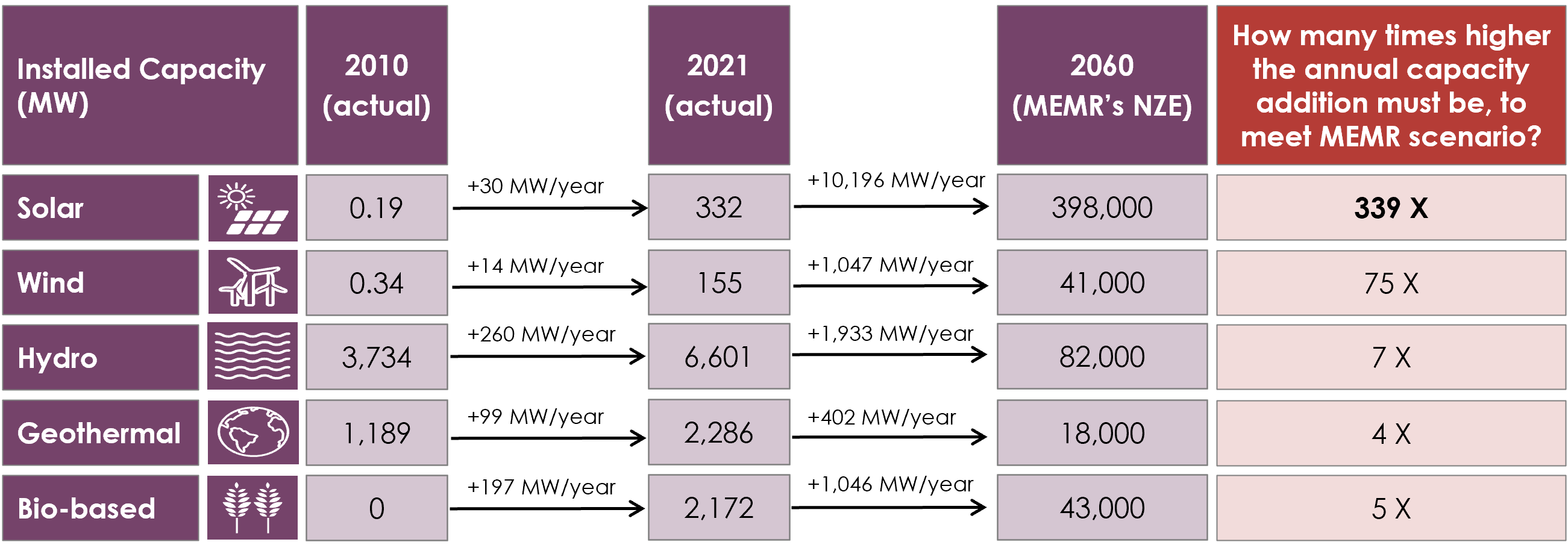

The NZE scenario, as outlined in the MEMR roadmap, also requires an exponential increase in renewables capacity. From 2010 to 2021, the installed capacity of renewables only grew by around 600 MW per year. Under the NZE scenario, solar energy is projected to make up the largest source of renewable energy, with a target of 398 GW solar-installed capacity by 2060. This raises the need for an expansive growth of solar power by 10,196 MW annually, which towers over its annual growth average of 30 MW from 2010 to 2021. The largest renewables capacity growth was seen in hydropower capacity, which grew by 260 MW annually, followed by bioenergy (197 MW) and geothermal sources (99 MW), for the same period (Figure 3).

Figure 4. RE capacity additions since 2010 vs. targeted capacity addition to meet NZE scenario

The capacity gap translates to a projected annual financing gap of USD 13 billion per year for renewable energy generation, with the widest gap being in solar and hydro, each accounting for USD 4.6 billion of annual gap.

Aligning Power Sector Finance with Indonesia NZE 2060 Commitment

Based on our tracking and analysis, we recommend the following policy actions to better align power sector finance with Indonesia’s NZE 2060 target and to strengthen the country’s capacity to speed up its energy transition:

- Accelerate investment in renewables, by:

- Realigning financing from high-emitting sectors and technologies to renewable energy infrastructure and technologies, such as a build-out of smart grid infrastructure and energy management system. This will better support the 35 GW power generation program, improve reliability and efficiency of power transmission and distribution, and help accelerate the electrification process.

- Scaling up investment in rooftop solar to unlock its huge potential. This should be supported by consistent MEMR regulation and state-owned electricity firm PLN policies that allow up to 100% feed-in tariff to anticipate increased demand for residential solar. Current installation of solar is hampered by a system quota (only 10-15% for residential and industrial customers), therefore limiting power surplus for customer bill deduction, changing the usual 5-hour charging to a first-come first-served basis, and imposing the switching rules among existing customers for a certain amount of time due to grid overcapacity. The issue of grid overcapacity should further be addressed by reducing power supply (managed retirement of coal-fired power plants) instead of restricting renewables.

- Divest from fossil fuels, by phasing down financing for fossil fuel power plants to avoid stranded asset risk. Given Indonesia’s 2023 deadline for no new commitment on coal-fired power plants and the government’s intent to explore early retirement of coal-fired power plants by 2040, financiers need to also consider re-alignment of financing policies and practices to support Indonesia transition to net zero. Such realignment should further be based on ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 2 (ATSF V2) that further caters to the high-emitting sectors, such as coal and industries, to adopt low-carbon technology which enables an orderly transition. In this regard, future iteration of Indonesia Green Taxonomy 1.0 should also be aligned with the ATSF V2.

- Address capacity gap, by issuing more streamlined policies and regulations on renewables. Capacity gap reflects the issues of uncertain regulatory environment and investment framework, rendering underdevelopment and underinvestment in renewables. A more robust enabling environment could redirect investment to narrow the gap. This includes increased effort to facilitate a better-functioning procurement process and fair competition in the power market. For example, the long-awaited draft of a presidential decree on procurement issues (e.g., centralization of procurement authority and direct appointment in the procurement process of electricity from renewable energy power plants), higher feed-in tariffs for renewable energy projects below a certain capacity, and competitive auctions for larger capacity project, have yet to be addressed, thus heightening investment risks, whether real or perceived.

- Unlock more opportunities to finance by leveraging various finance mechanisms, such as:

- “Energy Transition Mechanism” country platform that provides support for energy infrastructure and accelerates the clean energy transition (Indonesia MoF, 2022),

- De-risking facilities to lessen project risk and increase private sector participation in renewable energy projects, and

- Green bonds and sustainability-linked bonds, as a potential instrument to channel significant volumes of capital into renewable energy. Moreover, there is an opportunity to leverage more finance from JETP, as its financing model is envisioned to expand the access to both public and private finance, as well as catalytic and concessional finance to scale up investment for the energy systems.

These policy actions should then come with a critical note on Indonesia’s JETP. As the world’s largest energy transition funding partnership[3] to date, this initiative is expected to mobilize at least USD 10 billion of public finance from the International Partners Group (IPG) and another USD 10 billion of private capital facilitated by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). Given this strategic momentum to phase out coal-fired power plants, streamlined policy and regulatory frameworks are therefore becoming more urgently needed to align Indonesia power sector finance with the NZE transition plan and significantly improve the bankability of renewable energy projects.

[1] CPI. 2021. Improving the impact of fiscal stimulus in Asia: An analysis of green recovery investments and opportunities. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/improving-the-impact-of-fiscal-stimulus-in-asia-an-analysis-of-green-recovery-investments-and-opportunities/

[2] CPI. 2021. Blog: Indonesia wants a carbon tax, but with subsidies? https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/blog-indonesia-wants-a-carbon-tax-but-with-subsidies/

[3] In comparison with similar partnerships that IPG entered with South Africa in 2021 for USD 8.5 billion (JETP South Africa) and with Vietnam in December 2022 for USD 15.5 billion (JETP Vietnam)