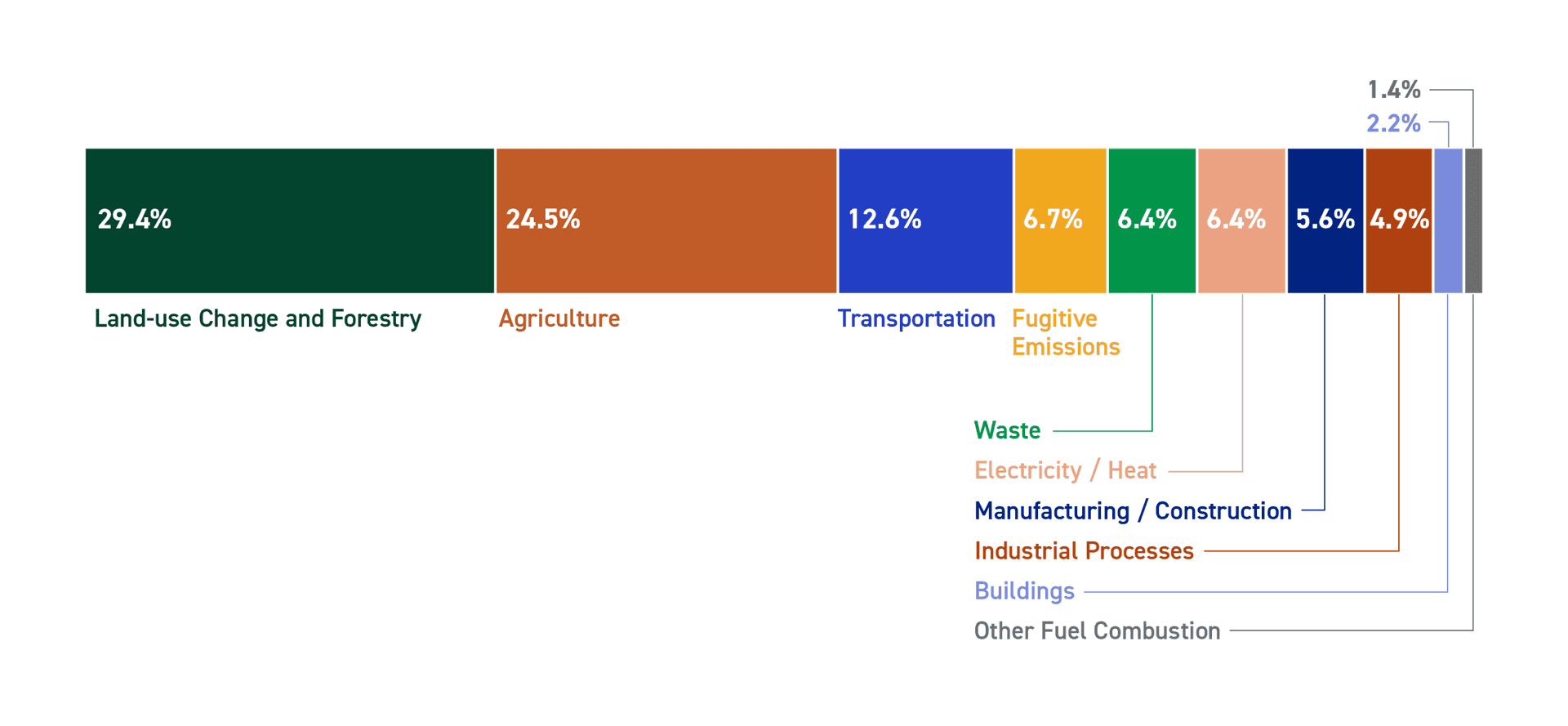

Agriculture, forestry, and other land use (AFOLU) is the largest source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), accounting for 55% of regional emissions, nearly double the global average of 30%. LAC is home to over 40% of the world’s animal and plant species, yet faces the highest rate of biodiversity decline globally, primarily driven by agricultural practices. Current farming and ranching practices are major drivers of deforestation and land degradation, consuming 75% of freshwater resources in the region, on which these species depend.

Figure 1: Share of emissions in Latin America and the Caribbean, by sector, 2021 (Source: Climate Watch)

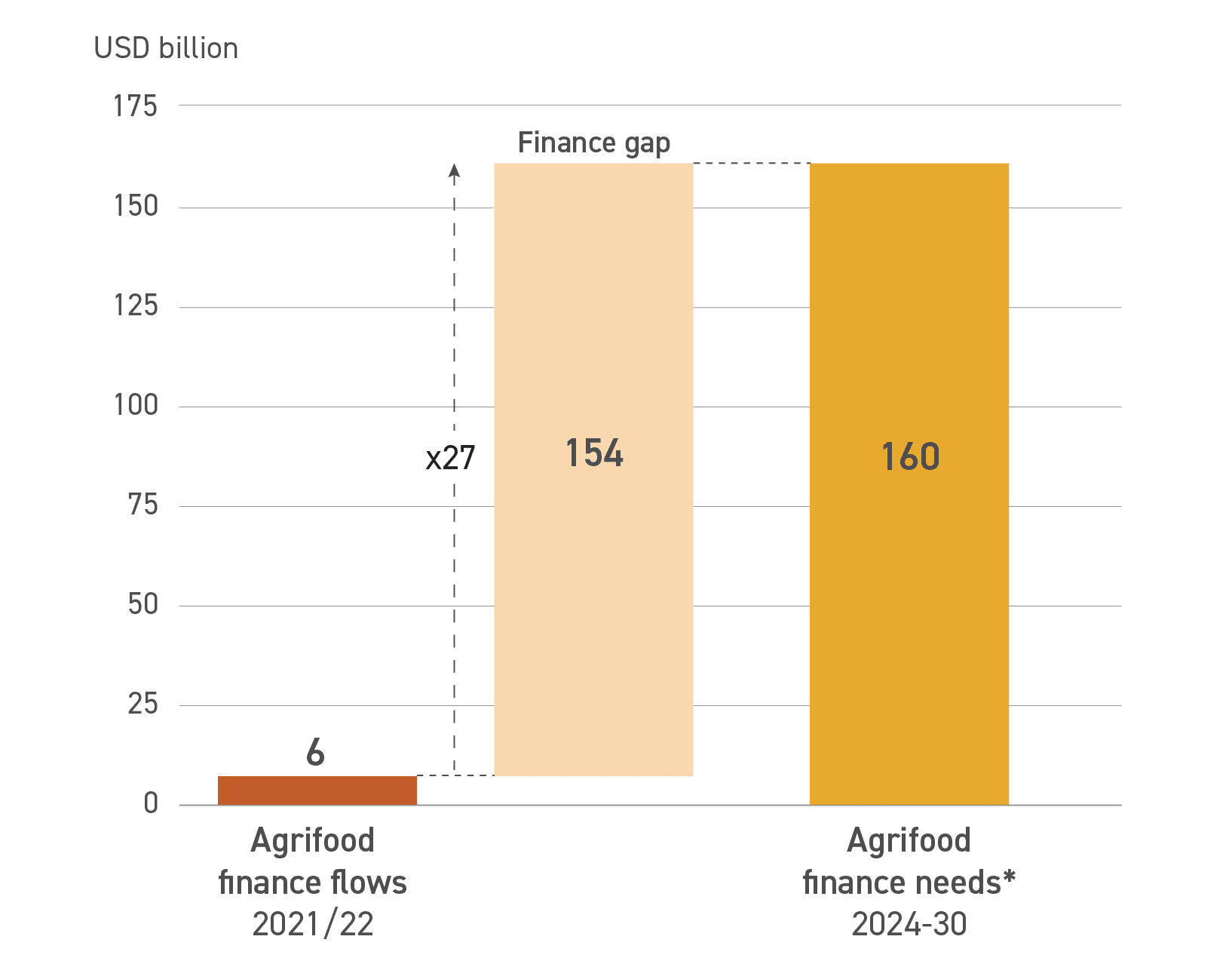

Several climate-related risks threaten the long-term viability of agrifood systems in LAC, including intensifying heat-related stressors, declining forage quality, and inadequate irrigation and water storage facilities. These risks will exacerbate as global temperatures continue to rise and weather patterns become increasingly unpredictable. However, despite the region’s high vulnerability to climate change and significant environmental footprint, LAC receives less than 5% of global climate finance for agrifood systems, or an underwhelmingly low USD 6 billion in 2021-22. The region requires USD 160 billion annually till 2050 – or 27 times more finance than current levels – to build the climate resilience of it agrifood system. To put this amount in perspective, USD 49 billion is needed annually just to combat land degradation in the region, while transforming LAC’s livestock systems alone will require over USD 25 billion annually.

Figure 2: Climate finance flows and needs for agrifood systems in Latin America and the Caribbean (USD billion, annual averages)

*This is an approximation based on CPI’s top-down global needs estimate for the agrifood sector (see CPI’s top-down climate finance needs methodology)

Multiple barriers limit the amount of climate investment in LAC’s agrifood systems. Perceived risks are high due to a lack of pipeline visibility, insufficient credit history, and currency and price volatility, while actual risks stem from governance, macroeconomic, currency, and geopolitical factors specific to LAC. Some barriers, such as underdeveloped financial markets and small-scale projects, have long hindered development finance in the sector. Others are more specific to climate-related projects, including limited technical capacities to assess climate impacts and the relevance of climate-smart practices, and misaligned perceptions of climate risks. These barriers are particularly challenging for private investors, who are further deterred by long investment horizons, small ticket sizes, and low returns.

Private finance accounted for only 2% of climate finance for agrifood systems in the region in 2021-22.

To date, the role of blended finance in catalyzing private investment for agrifood systems in LAC has been limited. As of 2024, USD 7 billion has been mobilized through 59 blended finance transactions, half of which went to agroforestry projects, concentrated in Brazil and Colombia. Strategies remain fragmented, leaving climae-vulnerable areas underserved, such as nature-based solutions (NbS) and smallholder finance (SHF). Transaction sizes for agrifood projects tend to be slightly smaller than those in other sectors, limiting their ability to scale. The limited availability of concessional capital prolongs pilot phases, while delaying deal structuring and capital deployment, especially for early-stage and higher-risk deals.

The potential of blended finance

The ClimateShot Investor Coalition (CLIC), Catalytic Climate Finance Facility’s (CCFF) Learning Hub, and Global Innovation Lab for Climate Finance (the Lab) recently collaborated with Convergence on a three-part webinar series to explore how blended finance solutions can harness private investment in LAC’s agrifood systems. CLIC members Root Capital and SAIL Investments, along with AGRI3 Fund—all experienced practitioners in the space—shared the following insights on designing blended finance instruments:

- Start with context: Effective investment in agrifood systems begins with a deep understanding of local contexts. This includes mapping the entire value chain, identifying prevailing practices, and assessing both the opportunities and barriers to transitioning toward more resilient and sustainable systems.

- Target key risks: Recognizing the range of financial risks and how these are distributed among actors is essential. In doing so, capital providers can determine where they are best positioned to add value, versus where they can solicit support from other actors. Targeting one or two key barriers with intention helps ensure additionality.

- Use layered approaches: A range of de-risking tools can be combined to align incentives and crowd in capital, such as technical assistance (TA), guarantees, first-loss tranches, foreign exchange hedging, insurance, and off-take agreements.

For instance, the AGRI3 Fund combines guarantees, which help structure long-tenor loans while protecting against currency depreciation, with TA, which is often essential to drive inclusion and impact for hard-to-reach smallholder farmers. In an emerging market like Colombia, this is particularly effective in helping local financial institutions expand lending while decreasing perceived risks for investors. Another illustrative example in Brazil is the Living Amazon Mechanism, which combines offtake agreements, which reach small-scale producers while mitigating their default risks, with anchor investors, who build legitimacy for the pilot and catalyze participation from other stakeholders.

To increase its effectiveness, blended finance structures must be tailored to the specific realities of local value chains, regulatory environments, and climate risks. Crucially, finance must be combined with capacity building.

In addition to this, recent work by CLIC, in collaboration with member ISF Advisors, highlights blended finance archetypes that have effectively mobilized investment in LAC’s agrifood system. Our Blended Finance Playbook for Climate-Smart Agrifood Systems outlines the following models that concessional finance providers have adopted in the region:

- Incubate and scale local financial intermediaries: Incubating multilateral financial institutions (MFIs) and rural banks can help expand appropriate lending services in underserved, climate-vulnerable areas. MFIs are best placed to assess local risk and are crucial for reaching last-mile actors across the value chain. Our research also shows that strengthening the capacities of local financial institutions (LFIs) can ultimately improve domestic finance mobilization.

- Support investments in local infrastructure and natural capital assets: Concessional capital providers are uniquely positioned to unlock investment in these areas, as they can address challenges involving structuring complexities, long payback horizons, and early-stage risks with approaches like aggregating projects and implementing equitable governance structures. For instance, blended finance can lower the cost of financing for capital-intensive infrastructure, such as renewable energy, warehousing, and storage, by offering risk-sharing and patient capital with flexible terms.

The path forward to scale

Coordination with policymakers and regulators will be critical to close the funding gap for LAC’s agrifood systems. When deployed at a system level, blended finance can address climate priorities and adaptation needs more effectively. Concessional finance providers can take the lead on an integrated public-private approach by aligning investments with national strategies, such as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs).

Proactively engaging with governments can help shape more granular investment plans, create co-financing opportunities, and attract foreign capital by mitigating regulatory risks.

CLIC’s climate finance roadmap also explores how policy and finance can work together to realign investment in LAC, with a focus on the livestock sector. The roadmap highlights how closing the investment gap requires addressing market frictions, policy failures, and structural risks to crowd in private capital. For example, market-based mechanisms can help adjust pricing and account for externalities, as seen in Colombia’s payment for ecosystem services system, which is creating new economic and regulatory incentives for private investors to finance nature.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and climate funds can further enhance impact by streamlining approval processes and targeting early-stage markets and vulnerable communities. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are amongst the most vulnerable countries in LAC to climate risk, yet struggle the most to attract financing. Strengthening public-private collaboration and expanding international concessional flows will be key to improving their resilience.

COP30 offers a critical opportunity to close financing gaps by making blended finance a core strategy in financing LAC’s agrifood systems. It is a chance for donors and development partners to align on robust financial and policy levers that can make agrifood investments bankable and inclusive. Blended finance will not be a silver bullet, but if deployed and supported well, it can play a pivotal role in shifting investment towards climate-resilient and nature-positive agrifood systems.