As one of Africa’s major economies and a growing GHG emitter, Nigeria is at a critical juncture in its development pathway. Investment decisions taken today will determine whether growth is sustainable and equitable for the rest of this century and beyond.

In spite of recent macroeconomic turbulence—including record-high inflation and currency devaluation—the country is working toward the key development goals of energy access, adequate water, sanitation and hygiene services (WASH), quality housing and infrastructure, sustainable agriculture, and access to health and education. Indeed, infrastructure investment needs are estimated at USD 3 trillion up to 2050 (World Bank Group, 2022) while the Government’s Energy Transition Plan (ETP) is costed at USD 1.9 trillion up to 2060 (ETP, 2022).

Climate risks across the country—notably flooding, sea-level rise, and drought— threaten to jeopardize Nigeria’s quest to achieve upper-middle-income status by 2050. Pursuing low-emission, climate-resilient growth can offer a viable means of delivering on development goals while ensuring the resilience of the infrastructure and ecosystems upon which the country’s growth will depend. To this end, the quantity and quality of climate finance will be key.

This study provides an update on CPI’s previous Landscape of Climate Finance in Nigeria. As part of CPI’s broader global climate finance tracking program, and a subset of the data presented in the 2024 edition of the Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa, this study aims to provide a robust baseline on climate finance flows in Nigeria, against which to measure and, in turn, better manage progress. It identifies opportunities in the Nigerian climate finance landscape, with a view to informing strategies to address barriers and scale finance mobilization at the pace required.

Key findings

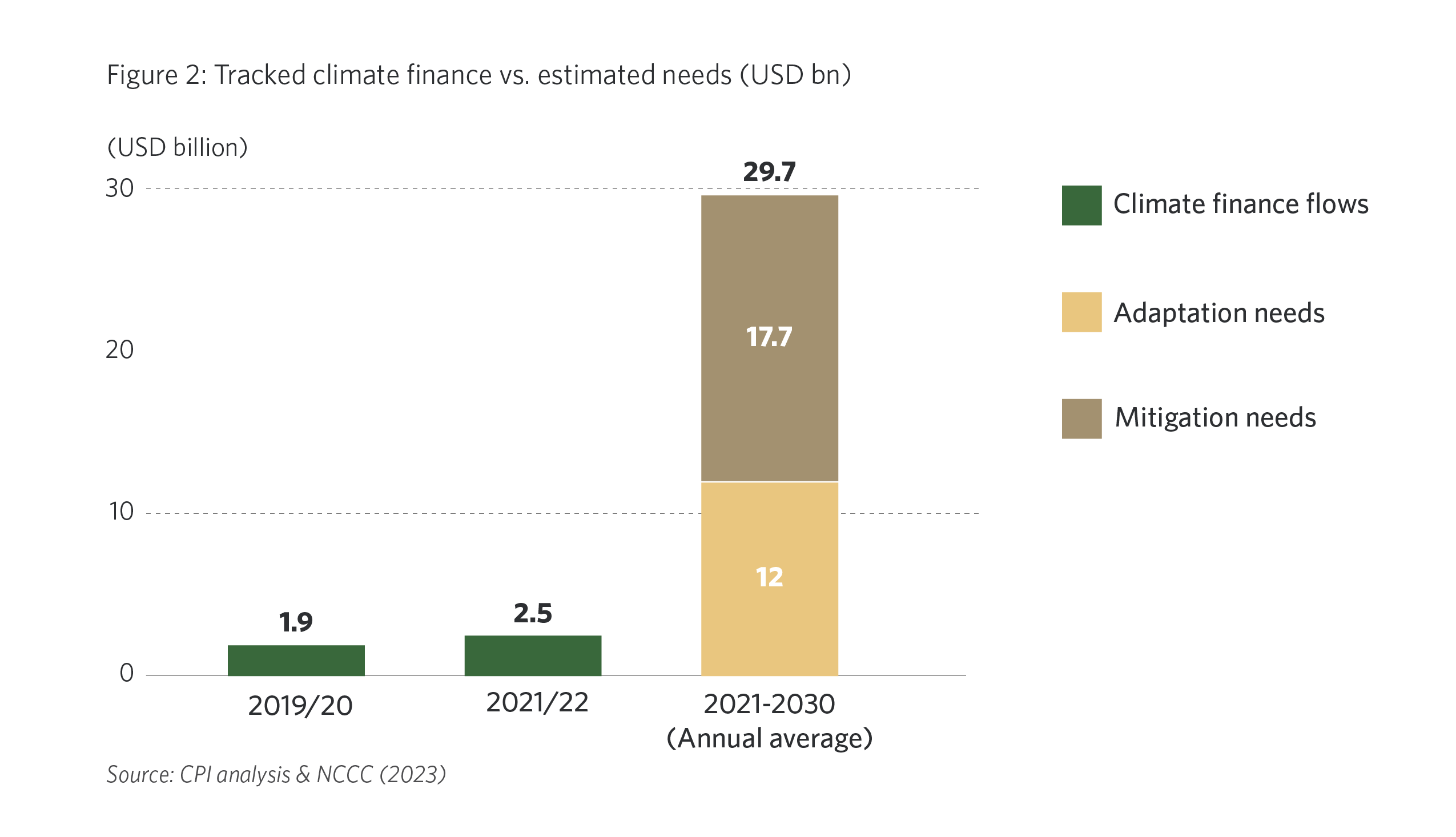

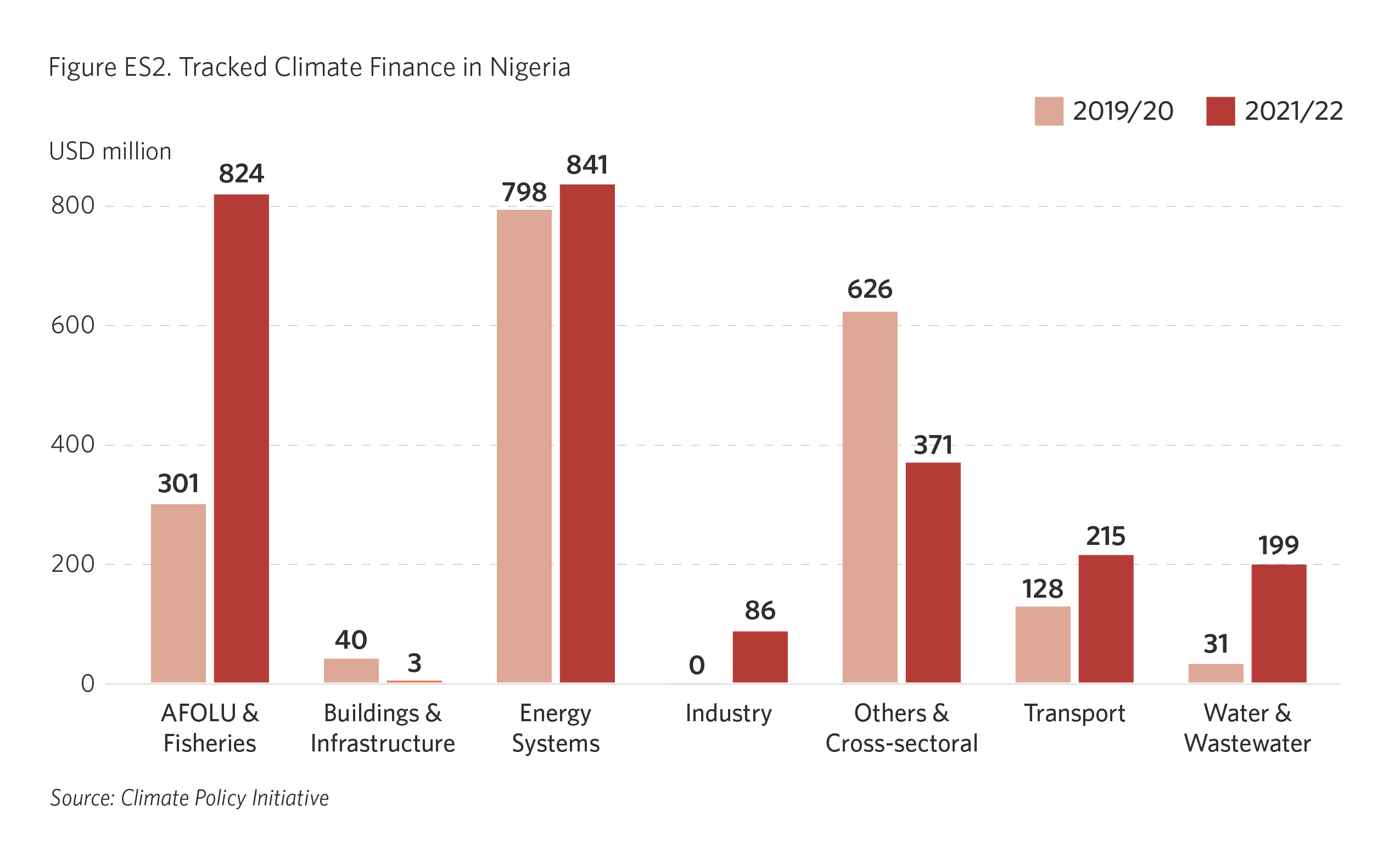

Nigerian climate finance witnessed incremental growth in 2021/22, the third-highest by total in Africa. However, flows fall well short of estimated needs. In 2021/22, USD 2.5 billion of public and private capital—from both domestic and international sources—went to climate action in Nigeria, up by 32% from USD 1.9 billion in 2019/20. Comparing flows to estimated needs, however, shows an annual climate finance gap of USD 27.2 billion.

Set in a broader context, and relative to opportunities for climate action, Nigeria’s USD 2.5 billion in tracked climate finance is minimal. Representing less than 1% of national GDP, this amount was almost equivalent to the country’s spending on foreign debt servicing in 2021/22 (USD 2.3 billion) (DMO, 2021; DMO, 2022). Moreover, climate finance flows were dwarfed by the USD 9.3 billion spent on government fossil fuel subsidies in 2022 (ODI, 2022) and the USD 6.7 billion in estimated loss and damage resulting from devastating floods across the country in the same year (UNDP, 2023).

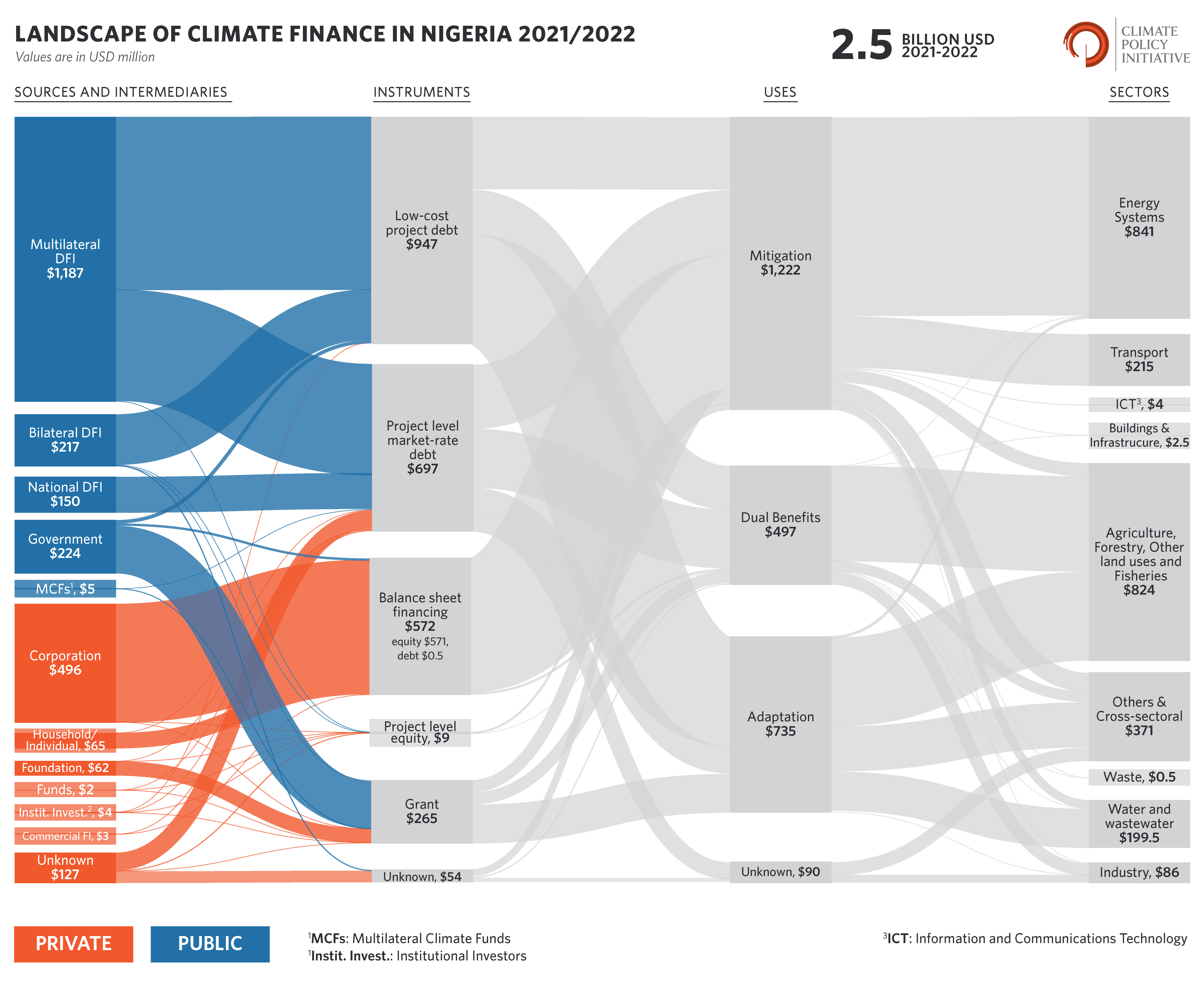

Public actors continued to provide most (70%) of Nigeria’s climate finance, though there was also relatively strong participation from corporations. Among public actors, multilateral development finance institutions (DFIs) were the largest providers (48%). Private actors provided 30% of total climate finance (up from 23% of the total in 2019/20) with corporations accounting for over three-fifths of tracked private climate finance. This placed the corporate contribution in Nigeria substantially higher than their share across African private climate finance as a whole (34%). Similarly, private actors provided a greater share of Nigerian climate finance (30%) than the African average (18%). Tracked corporate climate investments in Nigeria were largely for small scale solar PV.

Mitigation investments remained dominant in Nigeria’s climate finance landscape, totaling USD 1.2 billion, largely due to investment in solar PV. Despite the relative dominance of energy finance, the energy access gap remains a critical challenge for Nigeria, which has high growth potential for decentralized off-grid solar energy solutions. Other key mitigation opportunities include abating methane emissions by reducing gas flaring, which is widespread. In 2021/22 there was a significant uptick in low-carbon transport investments, while other key mitigation sectors—notably buildings, waste, and industry—are being left behind, receiving little-to-no finance.

Adaptation (USD 0.74 billion) accounted for less than one-third of Nigeria’s climate finance, covering only 6% of the country’s estimated adaptation finance needs, despite spiraling climate risks. Half of Nigeria’s adaptation finance went to the Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU) and fisheries sector. Water and wastewater adaptation finance grew significantly in 2021/22, but remains minimal relative to the scale of water stress throughout the country. Minimal-to-no adaptation finance was tracked for climate-resilient infrastructure for energy systems, buildings, transport, and industry. Overall, the financing gap for addressing flood risk is a major feature of the Nigerian adaptation landscape.

Dual-benefit finance—simultaneously reducing emissions and building adaptive capacity— accounted for 20% of Nigerian climate finance (USD 497 million) in 2021/22, indicating efforts to ensure the effective use of scarce climate finance. Most dual-benefit finance was for the AFOLU and fisheries sector, given the scope for climate-smart agriculture and sustainable resource management. There are also untapped opportunities for integrating nature-based solutions into (rapidly growing) urban spaces, offering potential to deliver a wide array of social benefits for Nigerian people, including improved air quality.

International public climate finance to Nigeria, which accounts for the bulk of flows, was largely channeled as debt, both concessional (54%) and non-concessional (35%). Reliance on debt-based climate investment is cause for concern, given the country’s already substantial debt burden. The Nigerian government spends over 80% of its revenue on settling or servicing debt, with only 20% of the remaining revenue available for spending on vital social services and development priorities (Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2023). At a more granular level, mitigation investments are channeled via a wider range of financial instruments—largely reflecting the commercial maturity of renewable energy technologies—compared to adaptation solutions, which are mainly funded by public debt.

In addition to the above quantitative findings, this study highlights key topics in the Nigerian climate finance landscape, including: subnational climate action, domestic climate budget tagging, mobilizing private finance through guarantees, mitigating gas flaring, and anticipatory adaptation.

Our research also identified the following challenges for scaling climate finance in Nigeria:

- Affordability of finance: The high cost of capital continues to stifle domestic and international climate investment.

- Bankability of projects: Limited supply of bankable projects – with sufficient scale and ticket size – deters investors from financing mitigation and adaptation.

- Capacity, skills, and awareness: A lack of awareness and understanding regarding the implications of the climate crisis, as well as the skills and capacity needed to address it, hinders the mainstreaming of climate action.

- Data and disclosures: Data gaps and limited data disclosures obscure the picture of progress and priorities for Nigerian climate action.

- Easy access to technology: A lack of affordable or locally appropriate green technology— for example, solar power components—inhibits the country from pursuing low-emission, climate-resilient growth.

- Fiscal incentives: Limited green fiscal incentives as well as the roll-out of pro-fossil fuel incentives undermines the impetus to invest in climate action.

Opportunities

Based on the Landscape findings, as well as insights from interviews with several expert stakeholders, CPI presents the following seven actionable opportunities to help overcome persisting challenges for climate action and work towards implementing green, resilient growth throughout Nigeria.

| No. | Agenda | Synopsis | |

| 1 | Step up project preparation support | Given the current absence of bankable project pipelines (that is, the mismatch between financial and technical project objectives) relevant actors (notably, DFIs and the Government) must step up project preparation support. | |

| 2 | Articulate investment-ready, well-integrated climate action plans | While the Nigerian Government has made progress in its climate policy and planning landscape, there is scope to provide costed and investment-ready climate action plans that are well-integrated with existing political, economic and social development priorities. | |

| 3 | Operationalize the National Climate Change Fund | Following the recent completion of technical proposals, it is essential to now operationalize the National Climate Change Fund. | |

| 4 | Build Nigeria’s domestic green industry | Subject to adequate technology transfer, there is an opportunity to build Nigeria’s domestic green industry, moving away from import dependence while creating jobs for a growing population. | |

| 5 | Prioritize anticipatory adaptation | Nigeria must prioritize anticipatory adaptation today—directly with the communities on the front line of the crisis—to avoid or minimize loss and damage later. | |

| 6 | Pursue innovative financing approaches | Risk mitigation instruments | There is a need for greater use of, and access to, innovative financing approaches that can tackle affordability constraints and unlock domestic capital. |

| Local currency financing | |||

| Green bonds | |||

| Debt-for-climate swaps | |||

| PAYG consumer financing | |||

| Insurance | |||

| Carbon finance | |||

| 7 | Better integrate climate and development priorities | Pursuing development priorities through a climate change lens is an imperative and an opportunity for delivering multiple benefits for Nigerian people, including through job creation, reduced air pollution and lower gender inequality. | |