Executive Summary

The Forest Code (Law No. 12,651/2012), one of Brazil’s most important environmental policies, balances the protection of native vegetation with agricultural production on rural properties. Essential to achieving the country’s climate goals and conserving biodiversity, the law also promotes sustainable forest management, the restoration of degraded areas, low-carbon agriculture, food security, and the adoption of nature-based solutions, all key pillars of a green and resilient economy.

Recognizing the Forest Code’s foundational role in advancing sustainable development in Brazil, Climate Policy Initiative/Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (CPI/PUC-RIO) has been systematically monitoring its implementation across Brazilian states since 2019. CPI/PUC-RIO researchers conduct detailed analyses of state-level regulations, collect and systematize data, and maintain ongoing dialogue with technical experts and public managers from state environmental and agricultural agencies through both in-person and virtual meetings. The result is an annual publication offering a comprehensive snapshot of the implementation of the Rural Environmental Registry (Cadastro Ambiental Rural – CAR) and the Environmental Compliance Program (Programa de Regularização Ambiental – PRA) across all Brazilian states, now in its seventh edition.[1]

The study applies specific indicators to highlight progress, gaps, and challenges observed over the past year. It also identifies successful strategies developed by leading states that can serve as models for others, while pointing out opportunities to accelerate the law’s implementation.

In October 2025, CPI/PUC-Rio released a preliminary version of this executive summary, containing data updated through August of this year, to inform climate discussions in the context of the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), held from 10 to 21 November in Belém, Brazil.

With the release of this full report, the executive summary has been fully revised. The data have been updated to reflect the progress achieved in recent months, including newly updated data and state-level implementation results, recent milestones in the federal governance of the National Rural Environmental Registry System (Sicar), and innovations announced in the context of COP30 itself. The aim is to provide an accurate and up-to-date overview of Forest Code implementation in 2025, grounded in the most recent information available.

COP30 reinforced the central importance of the forest–climate nexus in the international debate. Although negotiations did not advance toward defining a roadmap to curb deforestation, the conference highlighted instruments and initiatives that support the conservation of tropical forests, including the launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), which received initial pledges totaling US$ 6.7 billion.

The Forest Code stands as Brazil’s primary bridge between the climate and forest agendas. By establishing mandatory conservation rules—such as the protection of Permanent Preservation Areas (Áreas de Preservação Permanente – APPs) and the maintenance of Legal Forest Reserves on rural properties—the law integrates private lands into Brazil’s broader forest conservation framework. Furthermore, by requiring the restoration of illegally cleared areas, the Forest Code provides the foundation for a structured, nationwide public policy for forest restoration. The target of restoring 12 million hectares, set out in the National Native Vegetation Recovery Plan (Plano Nacional de Recuperação da Vegetação Nativa – Planaveg) and more recently in the National Climate Plan (Plano Clima), depends directly on bringing noncompliant rural properties into environmental compliance.

Consolidating the Forest Code as a cornerstone of Brazil’s climate policy requires not only recognizing its potential but also strengthening its effective implementation. In 2025, progress was made at both the federal and state levels, with structural improvements in governance and technological systems, and at the state level, where authorities play a leading role in implementing the law on the ground.

Strengthening Federal Governance of CAR and SICAR

In 2025, the federal government’s role in managing the SICAR gained new momentum, with concrete advances in governance, infrastructure, and intergovernmental coordination. Led by the Ministry of Public Management and Innovation (Ministério da Gestão e da Inovação em Serviços Públicos – MGI), in collaboration with the Brazilian Forest Service (Serviço Florestal Brasileiro – SFB) and with technical support from Dataprev—a public technology company under the MGI— the system has been undergoing a gradual transformation, becoming an increasingly open, interoperable, and public-interest-oriented digital infrastructure. In this context, the CAR was recognized at COP30 as the first digital public good dedicated to climate action. This recognition opens the door for CAR-based approaches to be adapted or replicated by other countries developing land-management and environmental-monitoring systems.

This evolution marks a new stage in SICAR’s governance, now supported by stronger institutional arrangements and guided by a structured work plan with specific goals, timelines, and clearly defined responsibilities among the MGI, SFB, and Dataprev. Under this framework, the MGI oversees SICAR’s technological infrastructure and database, with a focus on interoperability and digital innovation. The SFB, the agency responsible for environmental compliance policy, defines the operational rules and technical specifications for modules related to the analysis of CAR registries and the operation of the PRA. Dataprev manages the system’s infrastructure under the MGI’s supervision, ensuring its stability and processing capacity while developing and maintaining modules in line with SFB guidelines. This clearer, more collaborative, and functional shared governance model has enhanced SICAR’s ability to respond to the demands of Brazil’s federative system.

After overcoming the critical stage of migrating SICAR’s technological infrastructure to Dataprev in 2024 and resolving the initial instabilities caused by this transition, federal efforts shifted to improving the quality of the registry database and continuously enhancing the system’s performance and flexibility. These efforts laid the foundation for a more stable, scalable, and interoperable platform, better equipped to meet future demands. Key improvements include increased processing capacity, integration of CAR with other public databases, and upgrades to SICAR’s architecture, such as modernizing the source code and preparing the system for new functionalities.[2]

In terms of data integration, the federal government made progress in advancing interoperability among SICAR, the National Rural Land Registry System (Sistema Nacional de Cadastro Rural – SNCR), and the Land Management System (Sistema de Gestão Fundiária – SIGEF). This interoperability allows these systems to communicate and exchange information in a standardized and secure way, helping reduce land tenure and registry inconsistencies, and improving the reliability of CAR data. As part of this effort, the federal government presented at COP30 the pre-popullated CAR, a functionality already operating within SICAR that uses integrated public data to pre-populate registrations. The tool facilitates both the initial submission and the correction of previously submitted information, improving the quality of the registry database and reducing input errors.

In addition, Dataprev has been improving technical routines to ensure continuous integration between SICAR and state-operated systems, while the SFB has hired consultants to carry out local diagnostics, propose solutions, and support enhancements to data integration.

2025 also brought significant progress in building a shared governance model with the states—one grounded in cooperation, transparency, and procedural standardization—with particular emphasis on the creation of the Interfederative Network for CAR Management and Innovation (Rede Interfederativa de Gestão e Inovação do CAR – Rede CAR). The Rede CAR has become a permanent technical forum for intergovernmental dialogue, promoting the harmonization of procedures, the exchange of experiences and best practices, and collaborative problem-solving to address common challenges in CAR registry analysis and environmental compliance. In the same spirit of strengthening federative cooperation, the government launched the COP30 Mutirão (Task Force) for the Forest Code, a federal initiative carried out in partnership with states and civil society organizations to accelerate the registration, rectification, and review of CAR records.

During this period, the SFB also continued to develop new SICAR modules. Recent deliverables include improvements to the Environmental Compliance Agreement module and a new parameterization feature for state managers. However, the most significant progress occurred in advancing the Environmental Reserve Quota (Cota de Reserva Ambiental – CRA) agenda.[3] Following a decision by Brazil’s Supreme Court that reopened the path for its implementation, SFB developed a dedicated CRA module within SICAR, consolidating the instrument’s status as both an environmental and financial asset of national scope. In

October 2025, the first CRAs were issued in Private Natural Heritage Reserves (Reservas Particulares do Patrimônio Natural – RPPNs) in the state of Rio de Janeiro, marking the full operationalization of the instrument within SICAR. This agenda continues to be carried out in coordination with the states, which play a central role in issuing and monitoring the quotas, including verifying the integrity of the titled areas.

In parallel, the SFB engaged with the financial sector to design mechanisms for registering and trading CRAs. This approach aims to ensure legal certainty and economic attractiveness, giving the instrument real potential to fulfill its dual purpose: compensating Legal Forest Reserve environmental non-compliance and economically valuing preserved or restored native vegetation.

ADPF 743 and its Effects on the Forest Code Agenda

The federal government’s management of the SICAR in 2025 was also affected by rulings from Brazil’s Supreme Court in the context of ADPF 743, a constitutional legal action aimed at protecting core principles and provisions of the Brazilian Constitution. Filed by the political party Rede Sustentabilidade in 2020, the case alleged government inaction in addressing the surge in wildfires and deforestation across the Amazon and Pantanal biomes. The final ruling, issued in 2024, obliged the federal government to present a detailed plan to improve and integrate federal land and environmental management systems—including SICAR, the Land Management System (SIGEF), the National Rural Land Registry System (SNCR), and the National System for the Control of the Origin of Forest Products (Sistema Nacional de Controle da Origem dos Produtos Florestais – SINAFLOR), among other territorial and environmental data systems.

This plan to integrate territorial and environmental data could help address one of the main bottlenecks in CAR registry analysis. Weak and inconsistent land tenure information remains a core obstacle. The Supreme Court’s decision prompted the formalization of a federal action plan with its own timeline, goals, and governance structure. Although initially limited to federal agencies, the plan was later expanded, by order of the Supreme Court, to include the participation of the states of the Amazon and Pantanal biomes in its governance. The creation of the Intergovernmental Group for the Development of Common Solutions, composed of representatives from state environmental secretariats, the Office of the Chief of Staff of the Presidency, and relevant federal agencies, gave the process an unprecedented political and strategic dimension, distinguishing it from technical forums such as the Rede CAR.

The states also submitted a plan to the Supreme Court, containing guidelines, goals, and priorities for implementing the CAR and the PRA. Although this document was not formally incorporated into the federal plan approved by the Court, it has served as a reference for discussions and technical meetings, signaling a willingness to build joint solutions. One of the guidelines agreed upon within the Intergovernmental Group for the Development of Common Solutions is the systematization and consolidation of state-level information into an Integrated Action Plan.

Although this arrangement is currently limited to the states of two biomes, the judicially driven experience of intergovernmental governance underscores the need to expand and institutionalize permanent mechanisms for federative coordination within the federal executive branch. While mediation by the Supreme Court has enabled important progress, fully strengthening the implementation of the Forest Code requires embedding this intergovernmental coordination more systematically into public administration, under the political leadership of the federal government.

Progress in the Implementation of the Forest Code Across States

The implementation of the Forest Code across Brazilian states continues to progress at an uneven pace. In 2025, states that had already made significant advances in previous years consolidated their progress, while new initiatives began to emerge in regions that had historically shown lower levels of activity.

Over the past year, the states that made consistent progress in processing CAR registrations were those that implemented automated systems, such as Alagoas, Amapá, Ceará, Mato Grosso, Minas Gerais, Paraná, Piauí, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. Automation made it possible to expand both the number of registrations being processed and the validation of CAR records for properties smaller than four fiscal modules (módulos fiscais – MF), when free of inconsistencies and in compliance with the law, as observed in Alagoas, Ceará, and Minas Gerais.

The most significant gains in validation, however, occurred in the states that adopted innovative tools to generate CAR data or automatically review it, along with procedural changes that eliminate the need for prior landowner approval, as in Mato Grosso, São Paulo, and, more recently, Paraná. These procedural innovations have been decisive in translating automation into concrete large-scale validation outcomes (Box 1).

At the same time, this progress highlights a new challenge: the lack of verifiable land tenure information within CAR, which has become one of the main obstacles to advancing CAR analysis. In Mato Grosso—one of the most advanced states in implementing CAR and PRA— it is estimated that around 30% of registrations show significant overlaps, that is, spatial conflicts between boundaries that prevent automatic validation and require rectification by landowners. When these corrections are not made, the process stalls. Integration between SICAR and the SIGEF could help mitigate this problem by enabling automated systems to identify registrations based on certified, georeferenced data. However, since the SIGEF database covers only a portion of rural properties—excluding most landholdings and uncertified properties—it will be essential to develop complementary solutions, including strategies to encourage, mediate, and facilitate the correction of overlaps.

Amid uneven implementation across the country, a regional analysis offers an overview of the states that have made the greatest progress, those that have recently resumed advances, and those where implementation of the policy remains limited.

In 2025, none of the Northern region states made significant progress on implementing the Forest Code. Pará focused its efforts on registering agrarian reform settlement plots and developing a new CAR management system, but made no meaningful progress in analysis. Rondônia recorded an increase in the number of environmental compliance agreements, while Acre, despite a slowdown in analyses, stood out for its greater capacity to bring areas into compliance. Other states recorded only limited progress: Amapá expanded the use of streamlined analysis but still faces challenges in validation; Amazonas reached the initial stages of PRA implementation, with the first environmental compliance agreements signed; Roraima’s regulation of the PRA was vague and unclear at the end of 2024 and has yet to implement it; and Tocantins indicated plans to move forward with automation tools.

In the Central-west region, Mato Grosso remains a leading reference and has consolidated its position as one of the most innovative states in implementing the Forest Code, showing steady progress in both CAR analysis and in environmental compliance. The pace has been more uneven in the other states. Mato Grosso do Sul continues to make steady progress on CAR analysis and is now working to organize environmental compliance projects that were voluntarily submitted before the official PRA module was in place, under a self-declaration format. Goiás recorded a significant increase in environmental compliance agreements, driven by state legislation that allowed the regularization of environmental non-compliance beyond the national legal cut-off date (2008). The Federal District, however, still has limited implementation capacity.

In the Northeast region, progress in 2025 remained concentrated in a few states. Alagoas and Ceará, which adopted streamlined analysis, were the only states to record consistent progress in CAR analysis, although both still have a large number of registrations awaiting landholder response to official notifications. Among the states that began analyses in 2024, only Piauí showed meaningful growth—still modest relative to its overall registry base. Piauí also started using streamlined analysis, but in a limited and small-scale manner. Maranhão, which had led the regional agenda in previous years, made no progress in 2025. Paraíba and Sergipe continued at a very slow pace, while Bahia remained the region’s largest gap, with no public data or concrete signs of implementation. PRA implementation advanced in the states where the program is operational: Alagoas doubled, and Maranhão quadrupled the number of environmental compliance agreements.

The Southeastern states—Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo—have already implemented all phases of CAR and PRA, consolidating the region as one of the most advanced in the country. This position was further strengthened in 2025 with the progress made in São Paulo, which recorded a substantial increase both in validated CAR registrations and in the number of rural properties entering environmental compliance, and in Minas Gerais, which consistently expanded the volume of CAR processing while aligning environmental compliance with productive development strategies. Espírito Santo, which had already registered and processed nearly all smallholder CAR records years earlier, advanced in the processing of properties larger than four fiscal modules and completed the integration of its state system into SICAR. Rio de Janeiro, in turn, established a more robust institutional strategy in 2025, enabling the acceleration of CAR processing, even though validation remains incipient. The state also advanced in the Forest Code’s economic instruments agenda by issuing the first Environmental Reserve Quotas (CRAs) in the country, in partnership with the SFB.

The Southern region showed a clear shift in its approach to the Forest Code agenda in 2025, after years of limited implementation. Paraná made extraordinary progress by expanding the use of automation, adopting mechanisms for automatic review of CAR records, and restructuring CAR governance, becoming the most dynamic state in the region and one of the fastest-advancing in the country. Despite this progress, the state continues to face legal disputes related to the Atlantic Forest, which still generate legal uncertainty around CAR processing. Santa Catarina took its first concrete steps to resume implementation after a long period of inactivity. Rio Grande do Sul signed a judicial agreement early in the year recognizing that grazing in native grasslands does not prevent their recognition as remaining native vegetation, enabling the issuance of a new decree that could unlock CAR and PRA implementation in the Pampa biome. Although these measures are at different stages, they reflect renewed institutional engagement and create conditions for more consistent progress in the region.

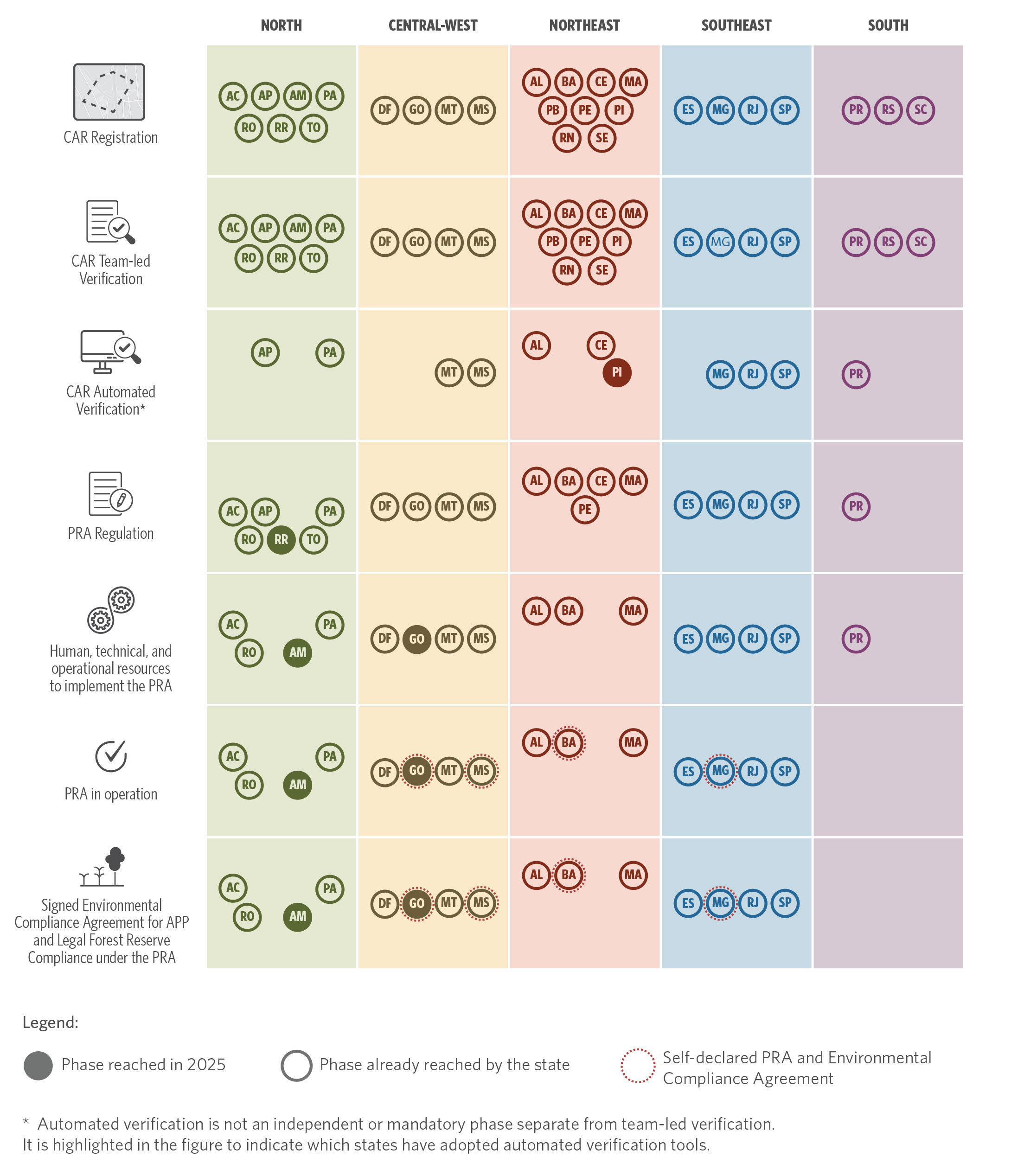

Overall, states have made more progress within the phases already underway than by advancing to new ones, which makes overall progress appear more modest than in previous years. Figure 1 below highlights the states that reached new implementation phases over the past year.

Figure 1. Implementation Status of CAR and PRA by State, 2025

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio, based on updated data provided by the state agencies responsible for CAR (as of November 2025) and the Brazilian Forest Service’s Environmental Compliance Dashboard (updated in November 2025), 2025

Registration in the CAR

Registration of Rural Properties in the CAR

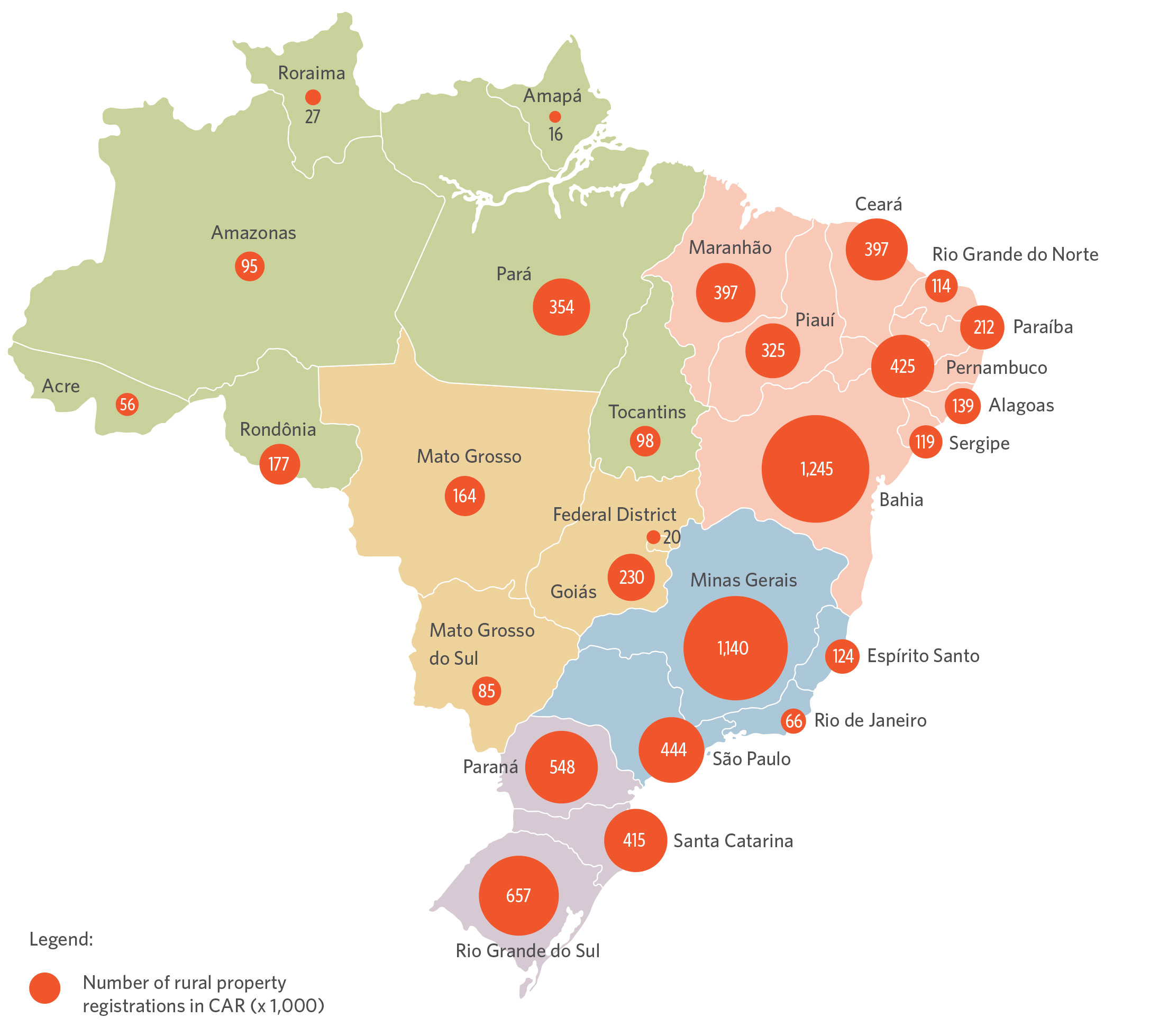

More than a decade after the creation of the CAR, the registration phase of rural properties has long been consolidated across all Brazilian states. However, the CAR database continues to expand. Over the past year, the national registry grew by approximately 5.6%, reaching just over 8 million CAR registrations. This increase was driven by the individualization of agrarian reform settlement plots, the inclusion of smallholders and Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLC) territories, and, most importantly, by the dynamics of subdivision, consolidation, and registration updates.

Bahia and Minas Gerais remain the states with the largest number of registrations, both exceeding one million (Figure 2). In Bahia’s case, this high number is directly linked to the registration model adopted by the state: in the State Forest Registry of Rural Properties (Cadastro Estadual Florestal de Imóveis Rurais – CEFIR), the state-level version of the CAR, registration is carried out by land title rather than by rural property. As a single property may comprise multiple titles, this approach significantly inflates the total number of records in the state database.

In general, the number of registrations in each state reflects its land tenure structure. More fragmented structures, dominated by smallholdings (minifundia), tend to generate a much larger number of registrations, creating additional challenges for managing, reviewing, and ensuring the environmental compliance of these records.

Figure 2. Rural Properties with CAR Registration, 2025

Source: CPI/PUC-Rio, based on updated data provided by the state agencies responsible for CAR (as of November 2025) and the Brazilian Forest Service’s Environmental Compliance Dashboard (updated in November 2025), 2025

Registration of IPLC Territories in the CAR

In 2025, the registration of IPLC territories in the CAR showed no significant progress compared to the previous year. The total number of registrations remained virtually unchanged. This scenario contrasts with the expansion observed in 2024 and indicates a stagnation in the inclusion of traditional territories in the registry.

Alagoas continues to lead in the number of CAR/IPLC registrations, currently reaching 1,467—about one-third of the national total. Maranhão (684), Bahia (612), and São Paulo (290) follow. Another three states—Minas Gerais, Paraná, and Pernambuco— each have between 100 and 200 registrations. Most of the remaining states still show very low numbers: Amazonas, Goiás, Pará, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Norte, Piauí, and Tocantins each have between 10 and 100 registrations, while all other states have fewer than ten. Particularly noteworthy is Mato Grosso, which, despite its significant presence of traditional communities, still has only one CAR/IPLC registration in SICAR.

However, the number of IPLC CAR registrations does not necessarily reflect the quality of these records. In Pará, specific projects and protocols involved workshops and training activities with the direct participation of communities, resulting in the registration of 72 IPLC territories covering about 4 million hectares and benefiting more than 20,000 people.

Individual Registration of Agrarian Reform Settlements Plots in the CAR

The individual registration of agrarian reform settlement plots in the CAR has evolved in recent years and is expected to expand significantly with the implementation of a new system in 2025. The CAR Plot Module (Módulo Lote CAR), developed in 2017 and made operational in 2023, gave rise to the Environmental Management System for Agrarian Reform Settlements (Sistema de Gestão Ambiental em Assentamentos da Reforma Agrária – SIGARA), which is scheduled to begin operating within 2025. SIGARA enables the individualization of settlement plots by cross-referencing multiple land tenure and environmental databases, producing more qualified registrations that include information on APPs, Legal Forest Reserves, land use, and the identification of beneficiaries for each plot.

Before data is submitted to SICAR, it must be validated by the beneficiaries, including the definition of the Legal Forest Reserve modality (individual or collective). Once implemented, the system is expected to scale up individualized settlement plots, though the requirement for prior beneficiary validation may become a bottleneck.

So far, approximately 13,900 plots across 264 settlements have been individualized through the CAR Plot Module, and these registrations will be incorporated into SIGARA’s workflow, which is currently being implemented. At the same time, states have been adopting their own methodologies: Pará validated more than 600 registrations in partnership with the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária – INCRA) and technical institutions; in Rondônia and Amapá, cooperation agreements enabled the preparation of individual registrations and the updating of land-use and cover information through participatory methods.

These experiences show that, although still in the process of national consolidation, the individual registration of settlement plots in the CAR is gaining scale and becoming a key instrument for integrating land tenure and environmental compliance in agrarian reform settlements.

CAR Analysis

The CAR analysis phase verifies whether the information provided by the landowner reflects the property’s actual conditions, in accordance with the criteria established by the Forest Code. Its purpose is to assess environmental compliance by identifying non-compliance or confirming that the property meets legal requirements. CAR data is processed by the state authority, with the procedure either conducted manually by a technical team or automated through systems such as the streamlined analysis module. If inconsistencies or missing information are identified, the landowner is notified to provide clarifications or make corrections. The verification, therefore, proceeds through successive cycles until the registration is officially “validated”.

In practice, many registrations remain for long periods within these intermediate verification cycles. To reflect this reality, this report distinguishes between two categories: (i) Under Review, referring to registrations that have entered the verification process but have not yet been finalized, and (ii) Validated, referring to those whose verification cycles have been completed and officially approved by the state authority.

Registrations Under Review

Although the registration phase has consolidated CAR as a key tool for environmental management, verifying the declared data is what gives the registry consistency and reliability—and this remains the main challenge on the agenda.

In 2025, the processing of CAR registrations advanced across several states, with clear effects at the national level. Between November 2024 and November 2025, the share of registrations under processing increased from 15% to 24% of the national database, reaching approximately 1.9 million records—an expressive gain, albeit unevenly distributed across states. The most significant progress occurred in those states that adopted automated processing systems—such as Alagoas, Amapá, Ceará, Mato Grosso, Minas Gerais, Paraná, Piauí, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo—even though each followed different paths in implementing these tools.

Paraná recorded one of the most significant advances in the country in 2025, after implementing a new CAR processing strategy and regulating automated procedures. The state carried out the processing with support from a specialized consulting firm, which made it possible to rapidly process a substantial share of its registry base. These results have not yet been integrated into the federal SICAR, as they depend on the completion of the technical integration procedures, expected to occur later this year. Amapá, a pioneer in adopting streamlined analysis, expanded the tool’s reach and processed more than half of its registrations. Alagoas, which had already been achieving excellent results in recent years, maintained its progress and now has nearly half of its registrations under review. Ceará made a remarkable leap, advancing well above the national average, driven by the full use of streamlined analysis. Minas Gerais experienced a sharp acceleration, with a substantial increase in the volume of CAR processing, driven by multiple strategies, including streamlined processing and reviews carried out by a contracted private firm. Rio de Janeiro recorded significant growth in 2025, after having only begun streamlined analysis on a small scale the previous year. Mato Grosso, which had historically ranked among the states with the strongest team-based processing capacity, restructured its strategy and, with the launch of CAR Digital, scaled up the process, significantly increasing the volume of processing and achieving notable gains in technical quality.

Mato Grosso do Sul, which had already advanced in automated processing in previous years, maintained a more stable pace in 2025, with only marginal growth. In general, this is due to the reprocessing of registrations already processed using more recent cartographic datasets, which improves quality without substantially altering totals. São Paulo presents a distinct situation: the state has already processed, through automation, virtually all registrations eligible for this phase, and, in 2025, focused its efforts on reprocessing its database through automatic rectification of declared information in properties of up to four fiscal modules. In states where CAR processing depends solely on technical teams, the number of processed registrations increases only when there is institutional reinforcement—whether through staff hiring, outsourcing, or delegating the process to municipalities. Even when progress is made, scaling up remains difficult in such cases.

Beyond differences in analytical strategies, a structural obstacle limits progress nationwide: land tenure conditions. States such as São Paulo and Mato Grosso have been able to apply automated analysis tools at scale because they have a large base of properties with consolidated and verifiable boundaries, supported by registries such as SIGEF. However, registrations with overlaps that exceed the legal tolerance threshold cannot move forward—whether through automation or team-led verification—until landowners make the necessary corrections.

Based on consolidated data over the years, São Paulo remains the state with the highest absolute number of registrations under processing, with 399,000 records. Paraná follows, with 284,000 records under review —an exceptional leap in 2025. Ceará comes next, with approximately 275,000 records being processed, the result of a sharp increase driven by the intensified use of streamlined processing. Pará also remains in a leading position, with roughly 253,000 analyses underway, reflecting different strategies adopted over the past decade. Minas Gerais follows, with about 180,000 registrations under processing.

Other states with substantial volumes of registrations under processing include Mato Grosso and Espírito Santo, both with around 95,000 records, as well as Alagoas, with roughly 66,000. Mato Grosso do Sul and Rondônia also stand out in this group, with approximately 58,000 and 54,000 registrations under processing, respectively.

Five states remain at an intermediate level, with 10,000 to 50,000 registrations being processed. Most saw only modest progress in 2025—such as Acre, Amazonas, Goiás, and Maranhão. Rio de Janeiro is also part of this group, although it recorded meaningful gains over the course of the year.

At the lower end, eight states and the Federal District have yet to surpass 10,000 registrations under processing—Amapá, Paraíba, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, Roraima, Santa Catarina, Sergipe, and Tocantins. In Amapá’s case, although the absolute number is small (9,000), it represents a major milestone for 2025, as it already corresponds to more than half of the state’s registry base. The most critical cases are Pernambuco and Rio Grande do Sul, each with just over one hundred registrations under review. Bahia remains a major gap, with no available data due to the specificities of its CEFIR system.

Absolute numbers help show the scale of the effort, but they do not fully capture the challenge each state faces. Because registry bases differ widely in size, the share of registrations under processing relative to the total provides a more accurate picture of each state’s implementation progress. This dynamic is particularly clear when comparing states with very large and very small registry bases: Minas Gerais, for instance, shows substantial gains in absolute numbers, even though its percentage remains relatively low due to the size of its database. Conversely, states with smaller registry bases—such as Amapá and Alagoas—show significant progress in relative terms, as more modest totals represent a large share of their overall registries.

Looking at these percentages, São Paulo leads with 90% of its registrations under processing, followed by Espírito Santo (77%), Pará (72%), Ceará (69%), Mato Grosso do Sul (68%), and Mato Grosso (58%). At intermediate levels are Amapá (54%), Paraná (52%), Alagoas (48%), and Amazonas (40%). Rondônia (31%), Acre (26%), Rio de Janeiro (17%), and Minas Gerais (16%) fall into a lower-intermediate group. In the remaining states, registrations under processing account for less than 10% of their registry bases.

Figure 3 shows the total number of registrations under review and their share in relation to the total number of records in each state.

Figure 3. Share and Total Number of CAR Registrations Under Review, 2025

![]() Interactive map

Interactive map

Note: Only valid registrations are included; analyses of canceled records were excluded.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO, based on updated data provided by the state agencies responsible for CAR (as of November 2025) and the Brazilian Forest Service’s Environmental Compliance Dashboard (updated in November 2025), 2025

Box 1. How São Paulo and Mato Grosso Innovated in the CAR Analysis Phase

The CAR analysis phase faces structural challenges. The adoption of a self-declaration system enabled the creation of a vast database of information on rural properties, but it also led to uneven technical registrations. Compared with more precise cartographic databases, many registrations present inconsistencies, such as overlaps between properties, incorrect delimitation of APPs, or inaccuracies in identifying consolidated rural areas—a portion of a rural property already occupied by human activities before July 22, 2008, including buildings, infrastructure, or agricultural, livestock, or forestry uses. The need for rectification by landowners, combined with communication barriers and missed deadlines, has led to a growing backlog of pending registrations and process bottlenecks.

In response, São Paulo and Mato Grosso have become national references by adopting distinct yet complementary solutions, both aimed at increasing scale, quality, and efficiency in CAR verifications.

São Paulo combined the customization of the automated analysis tool developed by the Brazilian Forest Service with regulatory adjustments to accelerate CAR verification. The state faced two main bottlenecks: low-quality registrations and the requirement for landholders’ prior approval. To address these barriers, São Paulo leveraged the system’s high-quality cartographic data to automatically correct smallholding registrations. In addition, a regulatory change reversed the approval process: the results are directly incorporated into the registry, while landowners retain the right to contest them afterward if they disagree. This combination of measures improved the process’s efficiency and scalability. The impact was especially evident in the validation phase: the number of validated registrations more than doubled—from 77,000 in November 2024 to 198,000 in September 2025—rising from 18% to 45% of the state’s total registry base.

Mato Grosso advanced through the creation of CAR Digital, which introduced an innovative approach by reconstructing registrations using the property boundaries already declared in the registry and integrating them with high-resolution cartographic datasets. This process rebuilds each registration by overlaying its perimeter onto updated spatial layers—such as land cover, hydrography, and topography—and automatically populates each property’s internal attributes with verified data. This integration produces more complete and higherquality registrations, automatically delineating APPs, Legal Forest Reserves, remaining native vegetation, and consolidated land-use areas. In 2025, with the statewide expansion of the tool, the launch of version 2.0 introduced a decisive change: it eliminated the requirement for prior approval by landowners. This regulatory adjustment significantly increased the scale of analyses, enabling faster, more consistent processing, though rectification is still required for cases of land overlap. As a result, the number of registrations processed more than doubled—from 45,000 (30% of the registry base) to 95,000 (58%). The effect was also evident in validation, as the share of registrations validated rose from 11% to more than 21% of the state’s total.

The experiences of these two states show that combining automation tools—capable of producing higher-quality registrations or triggering mandatory corrections—with procedural adjustments has been key to overcoming long-standing bottlenecks in CAR processing. At the same time, they demonstrated that sustained progress depends on robust technological infrastructure, reliable cartographic databases, and effective solutions to land tenure challenges that continue to prevent a significant share of registrations from advancing.

Validated Registrations

Validation of CAR registrations advanced to unprecedented levels in 2025. By November, approximately 724,000 registrations had been validated, corresponding to 9% of the national database—an expressive increase compared to the previous year, when only 3.3% of the database had been validated. Over this period, the country nearly tripled the total number of validated registrations.

As with the initial processing phase, automation played a central role in this progress, particularly in states that adopted structural strategies combining high-quality cartographic databases, automatic or compulsory rectifications, and the capacity to validate registrations without requiring prior approval from landowners. These factors were reinforced by adjustments to the tolerance thresholds for automated analysis, which had nationwide effects and enabled the validation of registrations that had previously been blocked due to minor cartographic inconsistencies—results that were especially visible in Ceará, Minas Gerais, Paraná, São Paulo, and Mato Grosso.

Despite this progress, major disparities remain: only a few states have validated a meaningful share of their registries; many remain below 5%, and nine states have not yet reached even 1% of validated registrations. Consolidating validation continues to be one of the main challenges for the full implementation of the Forest Code.

Paraná became the state with the highest number of validated registrations in 2025, after adopting automatic rectification with compulsory acceptance for properties of up to four fiscal modules—following the path pioneered by São Paulo. The automation strategy implemented in October and November enabled a rapid surge in validations, demonstrating the strong potential of compulsory rectification to deliver results at scale. However, its reach remains limited to registrations that can be fully processed automatically; larger properties or those with overlaps or unresolved inconsistencies still depend on complementary strategies, such as strengthening technical teams and improving communication to encourage landowners to correct their registrations.

Some states are also testing complementary approaches, including RetifiCAR — a program coordinated by the Brazilian Agriculture and Livestock Confederation (Confederação da Agricultura e Pecuária do Brasil – CNA) in partnership with state federations, rural unions, and environmental agencies. The initiative provides direct support to landowners in reviewing and correcting their registrations and has shown results in states that are still in the early stages of CAR processing. Because it operates at a small scale, the program cannot replace structural solutions, but it may play a strategic role as a complement to state-level efforts.

Espírito Santo stands out for validating 65% of its database. This result reflects the state’s long-standing strategy of providing technical assistance to smallholders during registration, through the Espírito Santo Institute of Agricultural and Forestry Defense (Instituto de Defesa Agropecuária e Florestal do Espírito Santo – IDAF/ES), which ensured higher-quality data from the outset. These validations were carried out in a state-level system that operated independently from SICAR, and until 2025 they were not reflected in the national database. Their integration this year finally allowed these results to be officially consolidated within SICAR.

As of November 2025, some states concentrated the highest absolute numbers of validated registrations. Paraná now leads, with around 220,000 validated registrations, followed by São Paulo with 198,000 and Espírito Santo with approximately 80,000. Next come Ceará (65,000), Minas Gerais (41,000), Pará (39,000), Mato Grosso (34,000), Mato Grosso do Sul (13,000), and Rondônia (11,000).

A group of states falls within an intermediate range, with between 1,000 and 10,000 validated registrations: Maranhão (7,700), Alagoas (5,300), Acre (2,700), Amazonas (1,600), and Rio de Janeiro (1,300).

At the lower end, several states have not yet reached 1,000 validated registrations: Amapá (922), Piauí (365), the Federal District (242), Goiás (182), Paraíba (82), Tocantins (77), Sergipe (62), Roraima (31), Santa Catarina (18), Rio Grande do Sul (14), and Rio Grande do Norte — with only six. Pernambuco remains the only state with no validated registrations. In Bahia, no data are available due to the specific features of its state-level system (CEFIR).

In percentage terms, Espírito Santo leads with 65% of its registry validated, followed by São Paulo (45%), Paraná (40%), Mato Grosso (21%), Mato Grosso do Sul and Ceará (both at 16%), and Pará (11%). Lower percentages are observed in Rondônia (6.1%), Amapá (5.6%), Acre (4.8%), Alagoas (3.8%), Minas Gerais (3.6%), Rio de Janeiro (2%), Maranhão (1.9%), Amazonas (1.7%), and the Federal District (1.2%).

All remaining states continue to show residual levels—below 1% of their registries validated—including Goiás, Paraíba, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, Rio Grande do Sul, Roraima, Santa Catarina, Sergipe, and Tocantins.

Figure 4. Share and Total Number of Validated CAR Registrations, 2025

![]() Interactive map

Interactive map

Note: Only valid registrations are included; analyses of canceled records were excluded.

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO, based on updated data provided by the state agencies responsible for CAR (as of November 2025) and the Brazilian Forest Service’s Environmental Compliance Dashboard (updated in November 2025), 2025

A key obstacle to validating registrations is the difficulty in establishing effective communication with landowners. In many cases, they either do not receive—or simply fail to respond to—notifications from state authorities requesting data corrections or additional information. As a result, a substantial share of registrations remains classified in SICAR as “awaiting response to notification”. This bottleneck persists even in states such as Amapá, Alagoas, and Ceará, which have made significant progress with automated analysis but continue to face delays due to pending corrections or unconfirmed approvals from landowners.

The new strategies adopted by São Paulo and Mato Grosso, discussed earlier, have proven effective in overcoming this barrier, but the challenge remains widespread. Several states have relied on temporary task forces to speed up CAR processing, which can produce short-term gains but fall far short of the scale required to accelerate validation nationwide. This situation underscores the need for a national communication campaign to increase producers’ awareness of the importance of keeping their CAR data updated in SICAR and responding promptly to notifications. Expanding communication channels (e.g., using WhatsApp in Mato Grosso or radio campaigns in Ceará) can broaden outreach and help speed up the verification process.

In addition to operational challenges, ongoing legal disputes continue to hinder CAR processing and slow the broader implementation of the Forest Code. The controversy over the concurrent application of the Atlantic Forest Law and the Forest Code in Paraná illustrates this problem. In 2021, Brazil’s High Court of Justice (Superior Tribunal de Justiça – STJ) suspended an injunction that required the state to apply the 1990 Atlantic Forest protection framework, thereby allowing CAR verifications to proceed under the Forest Code. However, in August 2024, the Court’s full bench reversed the earlier decision and reinstated the requirement to follow the Atlantic Forest regime—although the ruling has not yet been published and therefore remains unenforced.[4]

In parallel, the Federal Court of Paraná issued a final ruling in September 2024 consistent with the reinstated injunction, requiring compliance with the Atlantic Forest framework. In June 2025, however, this ruling was suspended by the Federal Regional Court of the 4th Region (Tribunal Regional Federal da 4ª Região – TRF-4), which cited the risk of serious harm to public order and economic stability.[5],[6] The suspension allowed the state to continue CAR analyses under the Forest Code framework, but pending a definitive judgment, the process remains under significant legal uncertainty.

The Paraná case exposes a genuine judicial standoff, with successive and contradictory decisions issued by courts at different levels. This back-and-forth reflects how the Judiciary has increasingly become an arena for political and strategic disputes surrounding the application of the Forest Code. The effects of this conflict extend beyond Paraná and could affect up to 17 states containing Atlantic Forest ecosystems, generating legal uncertainty for CAR verifications and environmental compliance across Brazil.

Cancellation of CAR Registrations in Public Lands Ineligible for CAR

The cancellation of CAR registrations overlapping Indigenous Lands, Protected Areas under public domain, and other areas ineligible for rural registration—such as undesignated public forests and other federal or state public lands—remains an important indicator of the Forest Code’s implementation. Several states—namely Pará, Acre, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Rondônia, and Roraima—have adopted measures to suspend and cancel irregular registrations in Indigenous Lands. Pará stands out for maintaining continuous enforcement actions and for publicly releasing geospatial data through an online dashboard.

At the federal level, 2025 brought further progress.Under the Territorial and Environmental Data Integration Plan approved by the Supreme Court in the context of ADPF 743, the federal government began implementing automatic filters in SICAR to identify and block attempts to register rural properties on federal public lands, as well as to require prior authorization from the competent authority before allowing corrections to registrations overlapping embargoed areas. Centralizing these controls at the federal level tends to make enforcement more effective, especially in the case of Indigenous Lands and other federal public lands, whose governance cannot rest solely with state authorities. Even so, monitoring state-level actions remains essential to assess concrete progress and ensure alignment with federal initiatives.

State-Level Regulation of the Forest Code

Regulation of the Environmental Compliance Program (PRA) and the Establishment of APP and RL Compliance Metrics

In the past year, Roraima enacted its PRA regulation, marking its first concrete step toward implementation. In total, 20 states and the Federal District have now regulated their PRAs, establishing metrics for implementing environmental compliance measures in APPs and Legal Forest Reserves. However, six states—Paraíba, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, and Sergipe— still lack the basic regulatory framework needed to implement environmental compliance.

Roraima’s PRA regulation introduced several innovations, including the incorporation of climate objectives, support for productive restoration, and a broad set of incentives to encourage producers to join the program. However, the law has a critical weakness: by failing to distinguish between pre- and post-2008 deforestation and omitting any reference to consolidated rural areas, it creates legal uncertainty and opens the door for all properties to be treated under the Code’s more flexible consolidation rules.

Other states have also introduced new regulations. Paraná updated its rules on APP and Legal Forest Reserve compliance. Rio Grande do Sul resolved its long-standing legal impasse over the Pampa biome and, following a judicial agreement, revised its decree to recognize that extensive grazing is compatible with the conservation of native vegetation and does not compromise the biome’s protection.

Pará, in turn, created an unprecedented—and controversial—mechanism for Legal Forest Reserve compensation by regulating the Environmental Protection Quota (Cota de Proteção Ambiental – CPA). The instrument was originally designed as a financing mechanism for the creation and management of Strictly Protected Areas. However, new state regulations expanded its scope to allow the CPA to be used for compensating Legal Forest Reserve deficits resulting from pre-2008 deforestation—the cutoff date established by the Forest Code for compliance. Under this arrangement, compensation is formalized through a temporary conservation agreement within the protected area associated with the quota. Because these areas are already subject to full protection, the agreement does not increase conservation outcomes; it merely creates a legal link that enables producers’ payments to be recognized as Legal Forest Reserve compensation. In practice, this expansion creates a shortcut to compliance: it allows producers to meet their obligations through a mechanism more flexible than what the Forest Code permits, while giving the state an additional source of revenue to finance the management of protected areas.

States such as Ceará, Minas Gerais, Paraná, and Santa Catarina have also created more robust governance structures to manage the CAR and/or the PRA, placing these agendas within higher-level institutions or involving multiple agencies. This institutional design strengthens the Forest Code agenda, enhances its political relevance within state governments, and promotes greater coordination with the productive sector.

Finally, between September 2024 and November 2025, nearly 40 state-level normative acts were issued, regulating procedures related to the CAR, the PRA, and the implementation of environmental compliance measures in APPs and Legal Forest Reserves—some complementing previous regulations and others replacing them.

Implementation of the Environmental Compliance Program (PRA)

The implementation of the PRA makes clear the Forest Code’s central challenge: moving from the identification of non-compliance to the actual restoration of APPs and Legal Forest Reserves. Although some states have made progress—especially those with greater capacity to process CAR registrations—participation in the PRA remains limited, and few compliance agreements are being formalized nationwide. Moreover, restoration efforts, whether ecological, productive, or multifunctional, require financial resources and technical capacity that are not always available, further limiting the program’s advancement. As a result, large-scale restoration of APPs and Legal Forest Reserves remains a distant goal in the short and medium term.

States have adopted different approaches to operationalize the PRA. Some have developed digital workflows that integrate CAR and PRA procedures, while others still rely on manual processes. A few states have introduced self-declaration models, in which landowners identify their own APP and Legal Forest Reserve deficits and submit a compliance plan even before their CAR registration is reviewed, as in Minas Gerais. Goiás uses the Environmental Declaration of the Property (Declaração Ambiental do Imóvel – DAI), a hybrid model that combines self-declaration with subsequent approval by the competent authority. Mato Grosso do Sul, in turn, adopted an early-submission model in which compliance plans were presented at the time of CAR registration. Although these approaches can lower initial barriers to participation, they have shown limited effectiveness at scale and often require later revisions to correct inconsistencies.

Implementation of the PRA saw concrete advances in 2025, especially through the rise in Environmental Compliance Agreements (Termos de Compromisso — TCs), which mark a producer’s formal entry into the program. The strongest progress occurred in states that had already established digital workflows and expanded their CAR analysis capacity. São Paulo, for example, more than tripled its number of agreements, while Mato Grosso continued to scale up an already consolidated program. Maranhão also stood out, quadrupling its agreements despite limited progress in CAR analysis. In most other states, gains were more modest, and among those that had not yet reached this stage, only Amazonas effectively began operating its PRA in 2025. Even with these advances, overall progress across the country remains far below what is needed.

Across the country, Mato Grosso remains the state with the highest absolute number of agreements, with 3,229 TCs signed. It is followed by Mato Grosso do Sul (1,552), Pará (1,199), and Acre (977). Next come São Paulo (800), Goiás (690), Maranhão (418), Rondônia (386), and Minas Gerais (204). At the other end of the spectrum, Alagoas (63), Espírito Santo (6), the Federal District (4), Rio de Janeiro (4), and Amazonas (3) show only incipient results, underscoring that consolidating the PRA remains a challenge for most states.

Figure 5 presents the performance of the states where the PRA is operational, comparing the number of validated CAR registrations with confirmed APP and Legal Forest Reserve deficits to the total number of TCs signed — the key indicator of progress in bringing rural properties into compliance with the Forest Code.

Figure 5. CAR Registrations Pending Environmental Compliance and Environmental Compliance Agreements, 2025

![]() Interactive graph

Interactive graph

Source: CPI/PUC-RIO, based on updated data provided by the state agencies responsible for CAR (as of November 2025) and the Brazilian Forest Service’s Environmental Compliance Dashboard (updated in November 2025), 2025

Acre stands out for effectively translating CAR validation into concrete environmental compliance outcomes, reflected in its comparatively high proportion of environmental compliance agreements. In São Paulo, by contrast, despite significant progress in both validation and agreement uptake, the share of properties enrolling in the PRA remains small relative to the overall pool of CAR registrations pending compliance. This gap illustrates one of the Forest Code’s key structural challenges: ensuring producer uptake once CAR validation is completed.

The comparison between the number of agreements and the area under restoration reveals sharp contrasts across states—especially when looking at the average size of each commitment. Although Pará holds by far the largest area under restoration, the most revealing contrasts emerge when comparing the average size of each environmental compliance agreement. In Amazonas, just three agreements cover 5,400 hectares—around 1,800 hectares per agreement—showing very large-scale compliance efforts per property. Rondônia presents a similar profile: 386 agreements span 56,800 hectares, an average of more than 140 hectares each.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are Acre and Minas Gerais, where commitments are much smaller. In Acre, 977 agreements amount to just over 2,000 hectares—roughly 2 hectares per agreement. In Minas Gerais, 204 agreements cover 1,800 hectares, averaging 9 hectares each. São Paulo and Pará fall in an intermediate range, with average areas between 30 and 90 hectares per agreement.

These contrasts make clear that counting agreements alone does not reveal the true scale of environmental compliance. In some states, a few commitments cover vast areas, while elsewhere dozens or even hundreds of agreements relate to small plots. Assessing PRA progress therefore requires looking at the actual hectares under compliance, not just the number of signed commitments. The figures on area under restoration were reported directly by state governments, and there are currently no public sources that allow these numbers to be verified or further detailed.

Environmental Compliance Monitoring

Monitoring verifies whether the actions set out in the Environmental Compliance Agreement (TC) are being fulfilled and whether restoration is progressing according to the timelines and methods defined in the TC itself. Although several states have already established procedures for monitoring compliance in APPs and Legal Forest Reserves, most still rely on self-monitoring by landowners through periodic reports, complemented by remote sensing analyses or field inspections by environmental agencies when considered necessary.

Only a few states have operational monitoring platforms, and even fewer have integrated geospatial systems capable of consolidating information on PRA implementation. Others are still developing their tools or have not yet reached this stage of the environmental compliance process. Technology—especially monitoring systems and geospatial data platforms—is essential for managing forest restoration and for making monitoring more efficient and transparent.

Alignment of the Forest Code with Other Public Policies

Strengthening the alignment between the Forest Code and other environmental and land-use policies is essential to increase its effectiveness. Integrating the CAR with conservation, restoration, deforestation control, land tenure regularization, and rural credit policies positions the CAR to serve not only as a monitoring and compliance tool, but also as an instrument that guides a broader sustainable development agenda.

A clear example of this alignment is Floresta+ Conservação, the federal Payment for Environmental Services (PES) program implemented in partnership with states in the Legal Amazon. Focused on conserving native vegetation, reducing deforestation, and maintaining environmental services in small rural properties and settlements, the program has worked closely with state agencies to advance CAR implementation. Joint actions have included field mutirões (task forces), training sessions, and support for processing, rectifying, and validating the registrations of potential beneficiaries. These efforts have already taken place in seven states—Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Pará, and Rondônia—and have resulted in 15,418 analyses, 5,535 rectifications, 10,076 validations, and 3,837 new registrations. These results show how the program can accelerate Forest Code implementation by linking CAR procedures to concrete conservation incentives.

State-level PES programs also reinforce this alignment. In São Paulo, the Refloresta-SP Program combines financial incentives for conservation and restoration with eligibility criteria based on CAR and PRA status, ensuring that benefits are directed to properties that comply with the Forest Code. Other state restoration initiatives use CAR data to identify priority areas and guide investments. Rio de Janeiro’s Florestas do Amanhã Program, which aims to increase native vegetation cover by 10% by 2050, relies on CAR information to orient its restoration strategy.

Deforestation control offers another important point of convergence. The state of Amazonas has developed a routine that cross-references deforestation alerts from the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe) with CAR data. When unauthorized vegetation suppression is detected, the state agency immediately suspends the CAR, imposes an embargo, and issues a fine. Other states—including Amapá, Espírito Santo, Paraíba, and Rio Grande do Norte—also cross CAR data with satellite-based alerts to identify responsible landholders and guide enforcement actions, although without suspending CAR registrations.

Finally, aligning the Forest Code with rural credit policy plays a strategic role in promoting more sustainable agriculture. Financial institutions have increasingly incorporated social and environmental criteria, restricting credit to properties with illegal deforestation or environmental embargoes, while expanding access or offering lower interest rates to producers with validated CARs and properties in compliance or in the process of compliance. Recent resolutions from the National Monetary Council (CMN) and the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) have reinforced this trend by conditioning credit limits on adherence to Forest Code rules and, more recently, prohibiting the financing of activities that involve native vegetation clearing. Despite representing important progress, these measures still lack robust monitoring mechanisms and effective sanctions, which limits their ability to fully drive environmental compliance.

This work is supported by a grant from the Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI). This publication does not necessarily represent the view of our funders and partners.

We would like to thank the representatives of federal and state agencies who contributed data and information, including: Acre, Alagoas, Amapá, Amazonas, Bahia, Ceará, Distrito Federal, Espírito Santo, Goiás, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais, Pará, Paraná, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Norte, Rio Grande do Sul, Rondônia, Roraima, Santa Catarina, São Paulo, Sergipe, MGI and its Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) Directorate, and the Brazilian Forest Service (SFB).

The authors would like to thank Ana Flávia Corleto and Giovana Souza for research assistance, Ana Flávia Corleto for translation work, Kirsty Taylor and Giovanna de Miranda for editing and revising the text and Meyrele Nascimento and Nina Oswald Vieira for formatting and graphic design.

[1] The Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) is Brazil’s national geospatial registry of rural properties. It records property boundaries, land use, Permanent Preservation Areas (APPs), and Legal Forest Reserves, and provides the basis for assessing whether rural properties comply with the Forest Code. The Environmental Compliance Program (PRA) is the pathway through which landowners address any environmental non-compliance identified in the CAR, typically by signing an Environmental Compliance Agreement (TC) that sets deadlines and methods for restoration.

[2] Source code is the set of commands and instructions that form the basis of a system and determine how it operates.

[3] CRA is the Forest Code’s tradable instrument for Legal Forest Reserve compensation, allowing landowners with forest surpluses to generate quotas that can be purchased by those with deficits.

[4] STJ – SLS 2950/PR (2021/0170590-0). Case record available at: bit.ly/42sMgno.

[5] TJPR – Civil Action no. 5023277-59.2020.4.04.7000/PR. Judgment available at: bit.ly/3VUw3ne.

[6] TRF-4 – SLS no. 5015462-83.2025.4.04.0000/PR. Decision available at: bit.ly/4n093PK.