Understanding how South Africa mobilizes, channels, and makes use of climate finance is fundamental to meeting development and climate goals. Climate finance flows are not only about scale, but also about where funds come from, how they move through our markets, and how they are directed towards the areas of greatest need, impact and return. Understanding and tracking these flows, over time is essential to inform evidence-based policy and investment decisions that deliver both climate and development outcomes.

Regulatory, policy, and financial shifts are reshaping South Africa’s climate transition, marking a decisive move from commitment to implementation. The country’s climate policy framework now closely aligns with national development priorities, reflecting two decades of progress in integrating climate considerations into economic and social planning. Internationally, South Africa has deepened its leadership in climate diplomacy. As G20 President in 2025, it continues to engage actively through the UNFCCC, BRICS, and the African Union to advocate for the priorities of developing economies. The country is also leveraging its Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) to mobilize concessional and blended finance, while championing multilateral development bank reform and debt-relief mechanisms to expand fiscal space for climate action, and contributing to global dialogue on the evolution of country platforms.

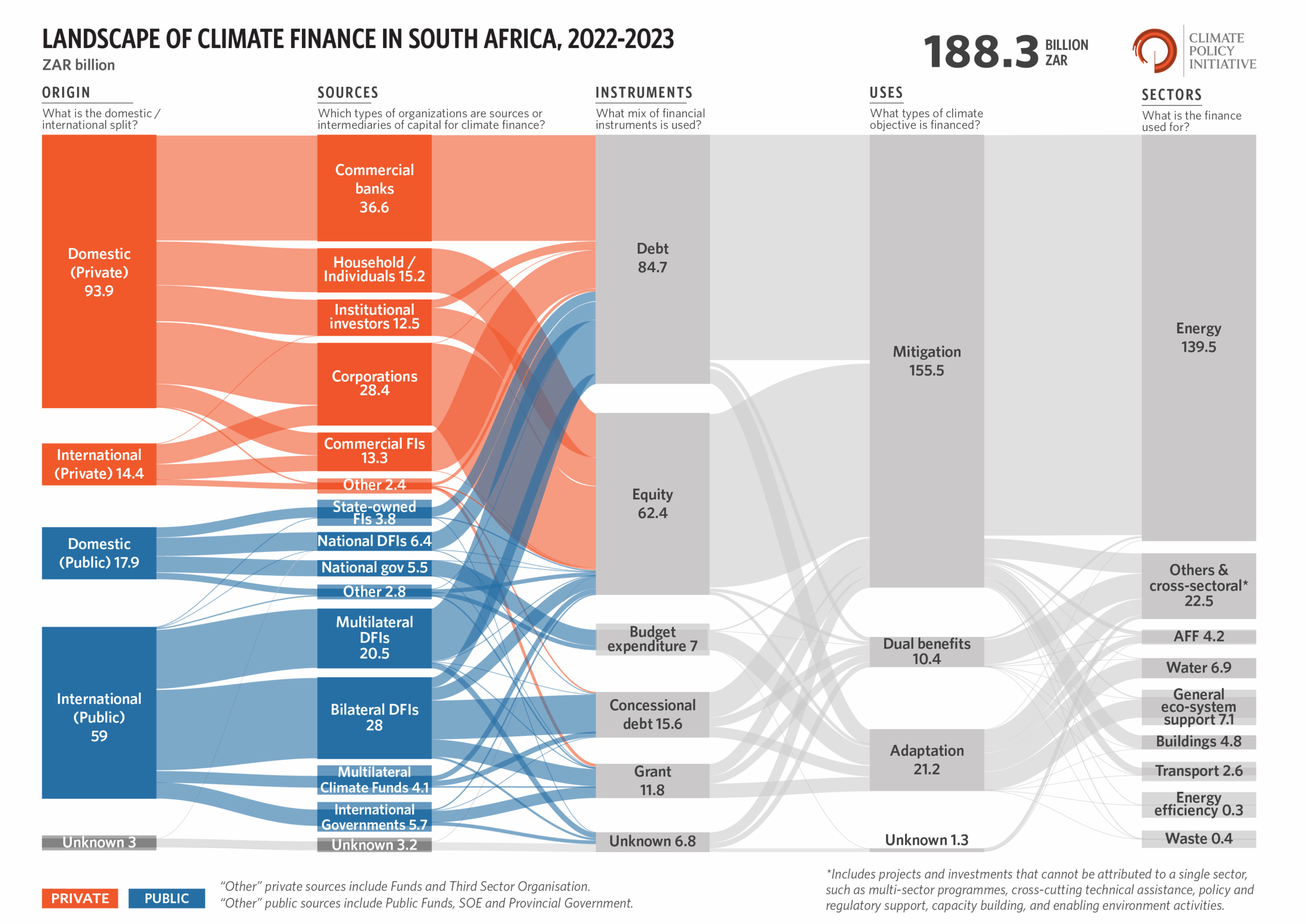

As South Africa advances its climate transition, tracking how resources are mobilized and deployed is critical not only to strengthen domestic and international decisions, but also to guide development finance institutions (DFIs) strategies, and inspire and inform other countries. The South Africa Climate Finance Landscape 2025 supports this effort by examining how climate finance was mobilized in 2022 and 2023, tracking flows for climate mitigation and adaptation solutions, as well as those with dual benefits across both mitigation and adaptation. This study tracks finance from both domestic and international sources, at both private and public levels, and indicates the instruments used to disperse those funds, ultimately identifying the sectors that benefited. This is the third iteration of the South African Climate Finance Landscape, following publications in 2021 and 2023.

This study is based on publicly available and proprietary data, sourced on a best-effort basis, to provide a comprehensive mapping of South Africa’s climate finance landscape. Methodological and data limitations remain, particularly on the periodic availability, quality, and robustness of information on private and public investment. To help address these gaps, this report uses CPI’s robust climate finance accounting methodology and adapts it to the South African context, complemented by insights from extensive interviews with market experts and stakeholders within the climate finance ecosystem. Notable improvements in this 2025 edition includes:

- Alignment of sectoral classifications with the South African Green Finance Taxonomy (SA GFT), published in 2022.

- Four new datasets and 16 additional domestic private and public-sector stakeholders, adding an annual average of ZAR 32 billion.

- Tracking just transition aligned climate investment.

Key findings

The 2025 Landscape tracked an annual average of ZAR 188.3 billion in climate finance for 2022-2023. Meeting NDC and net-zero targets will require at least two to threefold increase in current climate finance, with estimated needs reaching up to ZAR 499 billion per year. Actual investment requirements are likely higher, as most available estimates focus primarily on mitigation and energy investments, while adaptation needs remain under-costed.

South Africa is mobilizing climate finance at scale, but current flows are below needs. Adaptation and just transition finance, in particular, fall far behind the country’s vulnerability and policy ambitions. Climate finance flows, averaging ZAR 188.3 billion per year for the tracked period, sit at the intersection of energy security, fiscal constraints, and the evolving role of domestic and international capital.

- Energy dominates climate investment, with an annual average of ZAR 139.5 billion (74.1%) going into the sector, particularly for renewable electricity generation. This reflects the urgency of South Africa’s electricity crisis. In 2023 the country experienced record load shedding levels of more than 6,800 hours. The drive to stabilize supply has spurred investment into solar photovoltaics (PV), wind power, and battery storage. Policy changes, such as lifting the 100 MW licensing cap for private embedded generation in 2022 and introducing new wheeling frameworks in metros including Cape Town and Johannesburg, have enabled rapid private sector uptake. Falling global technology costs have reinforced this trend with utility-scale solar PV prices dropping by more than 80% between 2010 and 2023, making projects increasingly viable without heavy concessional support required. During the tracked period, key energy-related mitigation investments included solar PV (ZAR 64.8 billion, 47%), wind (ZAR 14.2 billion, 10.2%), energy storage (ZAR 14.0 billion, 10.1%), and off-grid renewables (ZAR 3.8 billion, 2.7%) annually. About ZAR 35.6 billion (25.7%) was classified as unspecified renewables, highlighting the need for further climate data tagging and granularity of sector-specific information.

- Adaptation finance is lagging. Only 11.3% of tracked finance supported adaptation, well below the African average of 33.7%, as captured in the Landscape of Climate Finance in Africa 2024, tracking years 2021–2022. Adaptation projects often generate public benefits, such as enhanced resilience and reduced vulnerability to climate risks, but typically lack clear revenue streams. This limits their attractiveness to private capital. In addition, many resilience investments are embedded within municipal budgets or take the form of small-scale initiatives, which are often harder to identify and capture in climate finance tracking. Fiscal constraints add to the challenge. With South Africa’s debt-to-GDP sitting at ~74% in 2024, and debt service consuming over 20% of expenditure, the government has limited room to scale adaptation finance despite growing climate risks. There exists a notable data gap in capturing adaptation finance in that national and provincial spend is captured in the Landscape methodology; however municipal spend is largely missing due to a lack of project-level tagging.

- South Africa’s climate finance mix reflects its middle-income country status. Market-rate debt (45.0% of total flows) and equity (33.1%) dominate, underscoring both the strength of the domestic financial sector and the central role of commercial actors. Domestic financial institutions, such as commercial banks, are seasoned project financiers, while corporates and households are increasingly investing in rooftop solar PV. However, high borrowing costs — with the repo rate reaching a 14-year high of 8.25% in 2023 — continue to constrain access to finance for municipalities and small, medium, and micro enterprises (SMMEs). Grid expansion, particularly transmission lines into new renewable energy zones, rural electrification, or grid-strengthening for variable renewables, involves large upfront capital costs, long payback periods, regulatory as well as off-take uncertainties. Concessional finance and grants collectively account for less than 15% of total climate flows. This leaves a gap for activities that require long-term, low-cost, or risk-tolerant capital, such as early-stage grid expansion, just transition support, and ecosystem restoration. While it is expected that private capital can fund much of the grid build-out, concessional resources are needed to de-risk large transmission investments, enhance grid readiness for renewable energy integration, and extend access to underserved regions.

- Nearly 60% of total climate finance flows originated from domestic sources. Commercial banks contributed an annual average of ZAR 36.6 billion (32.7% of domestic finance), corporations ZAR 28.4 billion (19.2%), and households ZAR 15.2 billion (13.6%). This reflects strong local market participation in advancing South Africa’s climate response, while also highlighting opportunities to attract greater volumes of international finance, particularly from private sources. However, currency volatility, macroeconomic headwinds, and regulatory uncertainty continue to weigh on foreign investor confidence and participation.

- Public sources dominate South Africa’s international climate finance flows. Bilateral development finance institutions (DFIs) provided an annual average of ZAR 28.0 billion, followed by multilateral DFIs (ZAR 20.5 billion), foreign governments (ZAR 5.7 billion), and multilateral climate funds (ZAR 4.1 billion). Collectively, these four intermediaries accounted for 79.2% (an annual average of ZAR 58.3 billion) of South Africa‘s total international climate flows. International finance was primarily channeled through market-rate debt (37.9%), equity (20.1%), concessional debt (20.8%), and grants (15.9%). The majority of international climate finance flows originated from Western Europe (71.2%), primarily reflecting commitments from the International Partners Group (IPG) under the JETP established in 2021. Despite the United States’ withdrawal from the IPG and the associated JETP in early 2025, renewed commitments from European partners have sustained momentum, keeping the JETP central to South Africa’s international climate finance landscape.

- South Africa’s just transition is emerging but modest. Over 2022-2023, tracked just transition-aligned flows averaged ZAR 16.0 billion, mostly sourced from government and DFIs. Private sector participation remains limited, constrained by an under-developed project pipeline and ongoing challenges in classifying social investments as climate finance. Actual spending on worker support, reskilling, and community development is likely higher than captured to date. This report’s tracking provides an initial snapshot of South Africa’s emerging just transition finance landscape, highlighting the need for more systematic data collection and clearer methodologies to assess how finance supports a fair and inclusive transition. The methodology is further explained in the Methodology Annex.

- Cross-cutting challenges continue to constrain outcomes. Grid bottlenecks in high-resource provinces restrict renewable rollout. Policy fragmentation, such as delays in updating the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) and uneven municipal permitting processes, creates uncertainty. Weak GDP growth and rising borrowing costs limit fiscal space and investor confidence for climate finance.

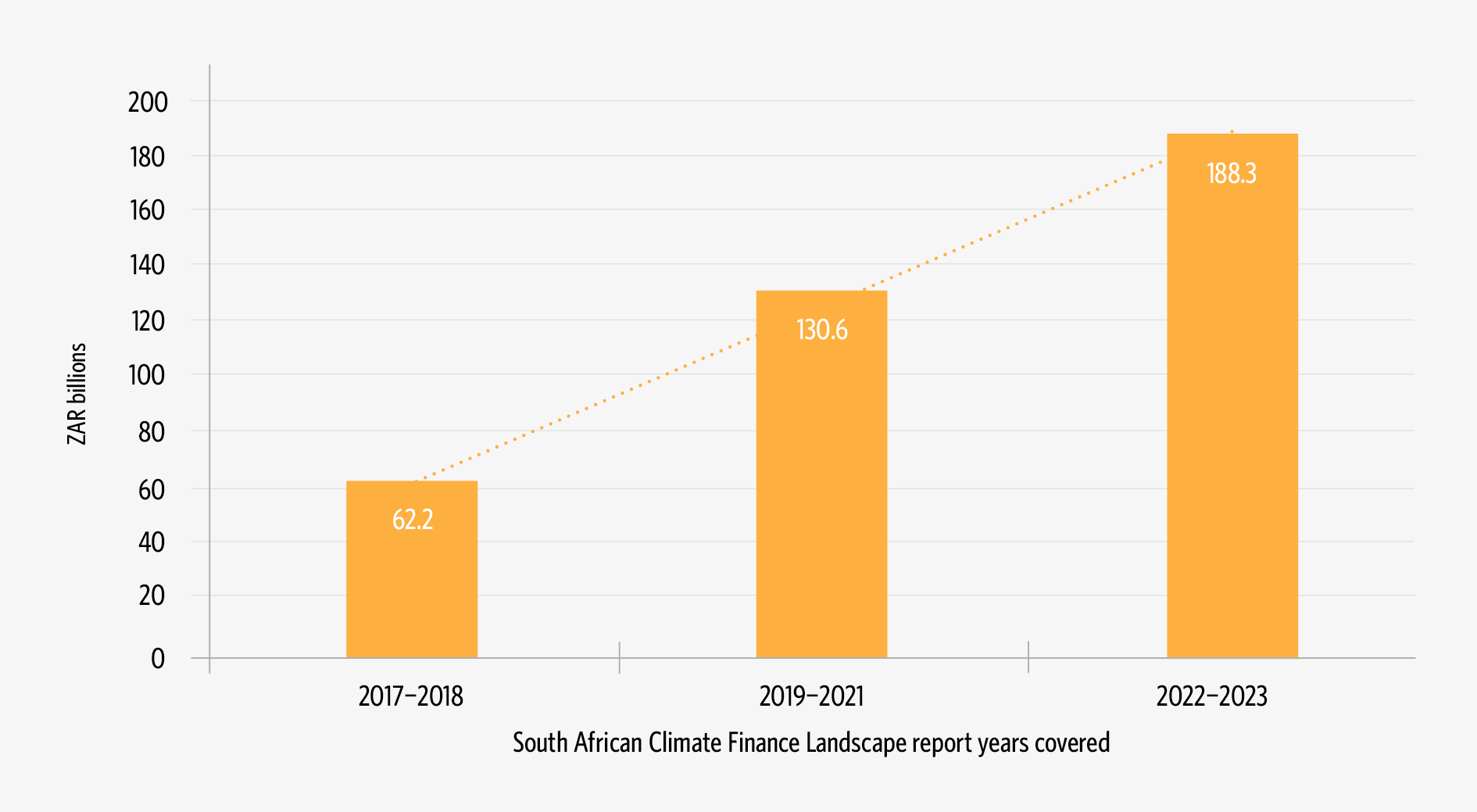

- The South African Climate Finance Landscape 2025, tracking years 2022–2023, highlights both significant progress and persistent gaps compared to previous tracking periods. As shown in Figure 2, the reported average annual climate finance flows increased from ZAR 62.2 billion in 2017–2018 to ZAR 130.6 billion in 2019–2021, and further to ZAR 188.3 billion in 2022–2023. However, direct comparisons between Landscape editions are indicative only and should be interpreted with caution, reflecting the current limitations of climate data tracking systems in South Africa and the evolving methodologies.